Why (and How) Global Economic Chaos Will Hit the Art Market in Ways You Might Not Expect (and Other Insights)

This week, stretching out the big picture…

Read Moreshining a light on the shadowy fine art industry

Image by Mediamodifier. Courtesy of Pixabay.

This week, stretching out the big picture…

Read More

If you don't already know who this is, you are either blessed or damned.

Photo by Duncan Hull. Courtesy of Wikimedia, via Creative Commons License.

This week, another sojourn into the cultural impact of social media…

Read More

A book that changed more than its author ever anticipated.

This week, another cautionary tale from the land of numbers…

Read More

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

This week, taking the long view…

Read More

A vacant storefront in Greenwich Village. Photo by Jason Tester. Courtesy of Flickr, via Creative Commons license.

This week, examining the state of late-pandemic real estate…

As of this column’s publication, it has been more than seven months since economic momentum started pushing more and more small businesses in the arts to scale up their square footage, particularly in New York City. But as the good times roll on the sales side, are the dealers and other art entrepreneurs increasing the size of their footprints also at risk of tripping straight into a buzzsaw?

By my count, north of 40 for-profit art businesses have now announced physical expansions of one kind or another since the start of the fall 2021 art season. The total is up more than 50 percent from when I last wrote about the new art-world space race this February. A slew of those upgrades have been sited here in New York City, with dealers who specialize in emerging art sizing up and spreading out just as eagerly as their blue-chip big siblings.

Yet evidence shows that the art businesses signing up for more space in New York are doing so despite prices surging back to pre-pandemic levels, if not beyond them in prime neighborhoods. Even worse, many, if not most, commercial landlords in the Empire City are determined to keep lease terms short to benefit from the market’s rise again as soon as possible—while leaving tenants more exposed than ever in one of the world’s most cutthroat real-estate markets.

This combination of factors doesn’t necessarily mean that dealers and art entrepreneurs made poor decisions by opting for architectural upgrades. Several will undoubtedly benefit (and some likely had no choice other than to grow). Still, an unblinkered view of the landscape makes plain that the New York art industry would do well to mobilize for permanent statewide regulation of commercial real estate before the next art-market downturn. Otherwise, the trade could very well be in store for the type of multilevel carnage avoided during COVID, but made all too real during the Great Recession.

Many of you are already painfully aware that residential real-estate prices in the U.S. have gone berserk in the late-pandemic era. Commercial real estate prices have largely followed the same trajectory due to the influence of similar market forces. However, their stomach-roiling return to orbit may come as news to almost anyone who hasn’t tried to lease a vacant storefront themselves in the past three quarters.

Why the discrepancy? Part of it has to do with a wide disparity in access to useful, reliable data on each sector.

The residential real-estate market is awash in noteworthy figures nationwide. In February, for instance, the Los Angeles Times relayed that the median rental price in the country’s 50 largest metro areas “rose an astounding 19.3 percent from December 2020 to December 2021,” citing research by listings site Realtor.com on properties with a maximum of two bedrooms. The U.S. Census bureau, meanwhile, found that only 5.6 percent of U.S. rental units needed tenants in Q4 of 2021, a smaller share than at any time since 1984.

Local data on residential real estate is ample and alarming, too. The New York Times reported that rents in New York City soared 33 percent between March 2021 and March 2022—almost twice the national average—based on data from the online rental aggregator Apartment List.

The total number of available apartments across the five boroughs peaked in August 2020, at nearly 76,000 units per online listings aggregator StreetEasy.com. By January 2022, that figure had plummeted by almost three-quarters, to less than 20,000. Supply in the city’s residential rental market has only dipped lower once since January 2016: In April 2020, the first full month after officials ordered nonessential businesses in New York to shutter.

But good luck finding comparable statistics on business leases in the Big Apple.

Even today, information on New York’s commercial real-estate market largely remains siloed by landlords and developers. The asymmetry largely forces brokers and potential tenants to cobble together whatever they can, whenever they can, however they can.

A recent transparency initiative has done relatively little to level the playing field so far. Inaugurated last year, the NYC Storefront Registry is a database that aims to track vital info on all of Gotham’s “ground-floor or second-floor commercial premises that are visible from the street and accessible to the public.” The data is supposed to include occupancy status, lease terms (if applicable), square footage totals, and much more, with all info updated quarterly.

As of this column’s deadline, however, the registry’s last update (on December 3, 2021) only contained data covering 2020, more than 14 months in the past. Earlier data releases were also riddled with inconsistencies, such as a failure to distinguish between the different reasons a storefront might be tenantless. (In fairness, this particular deficiency had been fixed in the version I reviewed.)

The office of New York comptroller Brad Lander recently added select data on commercial real estate to its monthly fiscal and economic outlook, but to me, the figures don’t offer much value.

The April 4 edition includes two entries: a chart showing the quarterly square footage and average asking rent of office property citywide (dating back to Q1 of 2018); and a table tracking Manhattan’s year-over-year retail availability rate in 11 different neighborhoods during the fourth quarter of the past three years.

Both visualizations are haunted by unanswered questions. How is the analysis defining “office” space, exactly? Are storefronts being lumped in with high-rise corporate towers? Why are percentages of available Manhattan retail space even useful to know, especially without accompanying data on prices?

In the end, dogged niche journalism may be the best tool for understanding New York’s commercial real-estate market. An impressively reported October 2021 feature by Kim Velsey in Curbed concluded that the state of play in this sector is at least as upsetting as late-pandemic results on the residential side:

Though the numbers fluctuate slightly by season and shopping corridor, the overall story is the same: Despite the closures and the changed nature of the city—despite everything—it costs about as much to rent a store in most neighborhoods as ever… There are more pop-ups, yes, and some new lease structures that might stick around, but retail landlords seem convinced that while there might be a few blips here and there, at the end of the day, the city only ever gets more expensive.

If you’re hoping the trends have improved in the past seven months, then brace yourself for an update from Paula Z. Segal, senior staff attorney at TakeRoot Justice, an organization that provides legal support to New York community groups pursuing equitable ends.

“Everything has only gotten worse,” she said.

Segal called commercial landlording in New York “the last unregulated industry”—ironically, a title that art professionals and analysts have been applying to the art market for decades. About half of the city’s residential units were rent-regulated circa 2018 (counting public housing), according to a municipal housing and vacancy survey. In commercial real estate, however, “everything is treated as a contract between equals, and there is no law” to limit price hikes, Segal said.

One artifact of this lawlessness is the chasm between the amount of publicly available data on the residential versus commercial property markets. Since state and local governments have no obligations to enforce regulations in the latter, property owners can hoard data with near impunity. Case in point, part of the problem with the NYC Storefront Registry may be that landlords are expected to self report their quarterly data or else face… the meager threat of a $500 fine.

The information asymmetry puts landlords in a position of extreme power. The harder it is for the consumer to even understand the severity of the problem, the harder it is to mobilize a coalition for change. No wonder so many galleries and other small businesses here still experience the hunt for new space as a hellish trial.

Elyse Derosia is one dealer thrilled to be done with the process for some time. Co-owner of newly expanded and rebranded Derosia gallery (fka Bodega), she and her colleagues needed a full year to find their new location at 197 Grand Street. So much about the process typified the broader struggles of New York small business owners across sectors.

“There was one brief little moment during COVID where landlords were freaked, and a few people got deals,” Derosia said. “But if anything, when I started looking in March 2021, landlords were digging their heels in because they could see the light at the end of the tunnel, and they were pissed because they’d lost money.”

After months of back and forth, Derosia eventually managed to sign an eight-year lease on the new space, at a rate that was more favorable in terms of cost per square foot than the basement unit where the gallery spent its previous seven years. But it only happened after a series of false starts and some hard-nosed bargaining.

“One of the biggest challenges was negotiating a lease for more than five years,” she said. “No one was willing to do 10 years. Eight felt like a triumph.”

Based on commercial lease terms elsewhere in the city, it was. Sources say that even the rare deals struck during the COVID-discount era were normally only for a year or two, allowing landlords to jack prices back up to market rates at the first opportunity. Velsey of Curbed also reported that post-pandemic commercial leases sometimes contain new safeguards for landlords stipulating that tenants would be responsible for paying full rent even during mandatory pandemic-related lockdowns.

In other words, one of the most notorious rental markets in the country has only gotten tougher since the pandemic. That fact throws yet another obstacle in front of small art businesses seeking to keep some soul and accessibility in the nation’s cultural capital. Still, one local proposition could work wonders for everyone in the arts, regardless of their size or market might.

In 2019, city councilman Stephen Levin introduced a commercial rent-regulation bill proposing the formation of a business-facing counterpart to New York’s residential rent guidelines board, which sets a new maximum allowable price rise for rent-stabilized apartments every year. To me, it’s a commonsense reform that incentivizes landlords and tenants to develop the types of long-term social connections being eroded by the profit motive. After all, if property owners can no longer price-gouge their current occupants to make way for drastically higher-upside replacements, the city might still avoid becoming an antiseptic megalopolis ruled by big brands and high-earners.

Segal of TakeRoot Justice, a staunch backer of Levin’s bill, emphasized that the commercial rent guidelines board would exert regulation, not control, over the market. Unlike its residential equivalent, the structure would empower commercial landlords and tenants to formally contest the decided-upon rent if they believe it deviates too far from the market rate in either direction.

“We don’t want to freeze rents that are unusually low or high,” Segal said. “We want landlords to be able to appeal the ruling to bring rates up, and tenants to be able to appeal to bring them down.”

In an industry so used to relying on self-regulation, Levin’s bill represents a rare opportunity for small businesses in the arts to solve a major problem by pressuring someone else to get their act together. With dozens and dozens of galleries committing to more exhibition space amid a booming market, New York dealers might think that calling a city councilman to support a niche proposal is nothing more than a distraction. (A spokesperson for the Art Dealers Association of America said the group had done no advocacy on the bill to date.) But no bull market lasts forever—and neither does any commercial lease.

[Curbed]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: the better things are going in the moment, the more important it becomes to plan for when they won’t be anymore.

The Instagram icon (duh). Image by TakipçiMatik. Courtesy of Wikipedia, via Creative Commons license.

This week, another detour in the democratization narrative…

Read More

Epic Games’s Fortnite booth at the e3 conference in 2018. Photo by Sergey Galyonkin. Courtesy of Wikimedia, via Creative Commons license.

This week, a reminder that you better play the game before the game plays you…

Read More

A mockup of offerings from the forthcoming Bored and Hungry burger pop up in Long Beach, California. Courtesy of Bored and Hungry.

This week, assessing whether you can incentivize your way to a sensation…

Read More

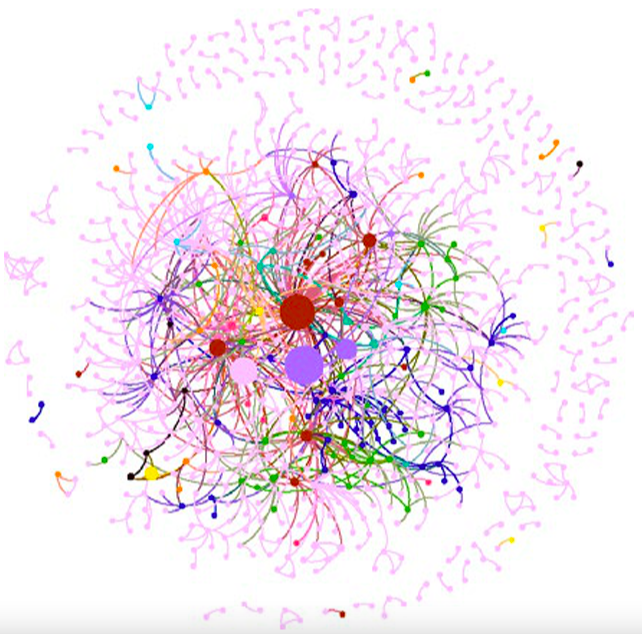

A data visualization of Foundation's collector network, with collectors as nodes and their joint NFT bids as links. The nodes are sized based on maximum investment. All but the top 10 collectors appear in pink.

Courtesy of Barabási Lab.

This week, a data-driven blueprint for crypto art sales...

A new study of the prominent NFT platform Foundation leverages crypto’s built-in candidness to answer a question foremost in the mind of every ambitious artist selling there (or anywhere): What is the recipe for market success?

The five laws clarified by the data may be able to help crypto artists improve their results on the platform. But they also lend support to the notion that the NFT market sometimes behaves much more like the legacy art market than many blockchain revolutionaries would like to believe.

Published in February in the journal Scientific Reports, the research was conducted by Barabási Lab, a team of artists and data scientists studying complex networks. It is the second analysis of a major NFT platform performed by the lab’s founder and namesake, Northeastern University professor Albert-László Barabási; he wrote about his research on SuperRare for the New York Times last May. (Barabási’s co-authors on the Foundation study are Kishore Vasan and Milán Janosov, the latter of whom also worked on the SuperRare piece.)

Studying Foundation, which launched in February 2021, provided an opportunity to focus on primary market data just as NFTs vaulted into the broader culture conversation via the $69.3 million sale of Beeple’s Everydays – the First 5000 Days at Christie’s that March. It is an understatement to say Foundation does not specialize in secondary sales; of the more than 48,000 NFTs originally listed for sale on the platform during the study’s course, a minuscule 138, or 0.2 percent, were actually resold there.

It’s vital to keep in mind that Barabási’s research into Foundation covers only about the first five months of its lifespan (ending June 18, 2021). Still, its five main findings about artistic success on the platform are clear and powerful. Based on what I know about how markets for art and collectibles tend to work, I’d also bet that they are more likely to stay ingrained for the long term than to fade out over time.

Here they are…

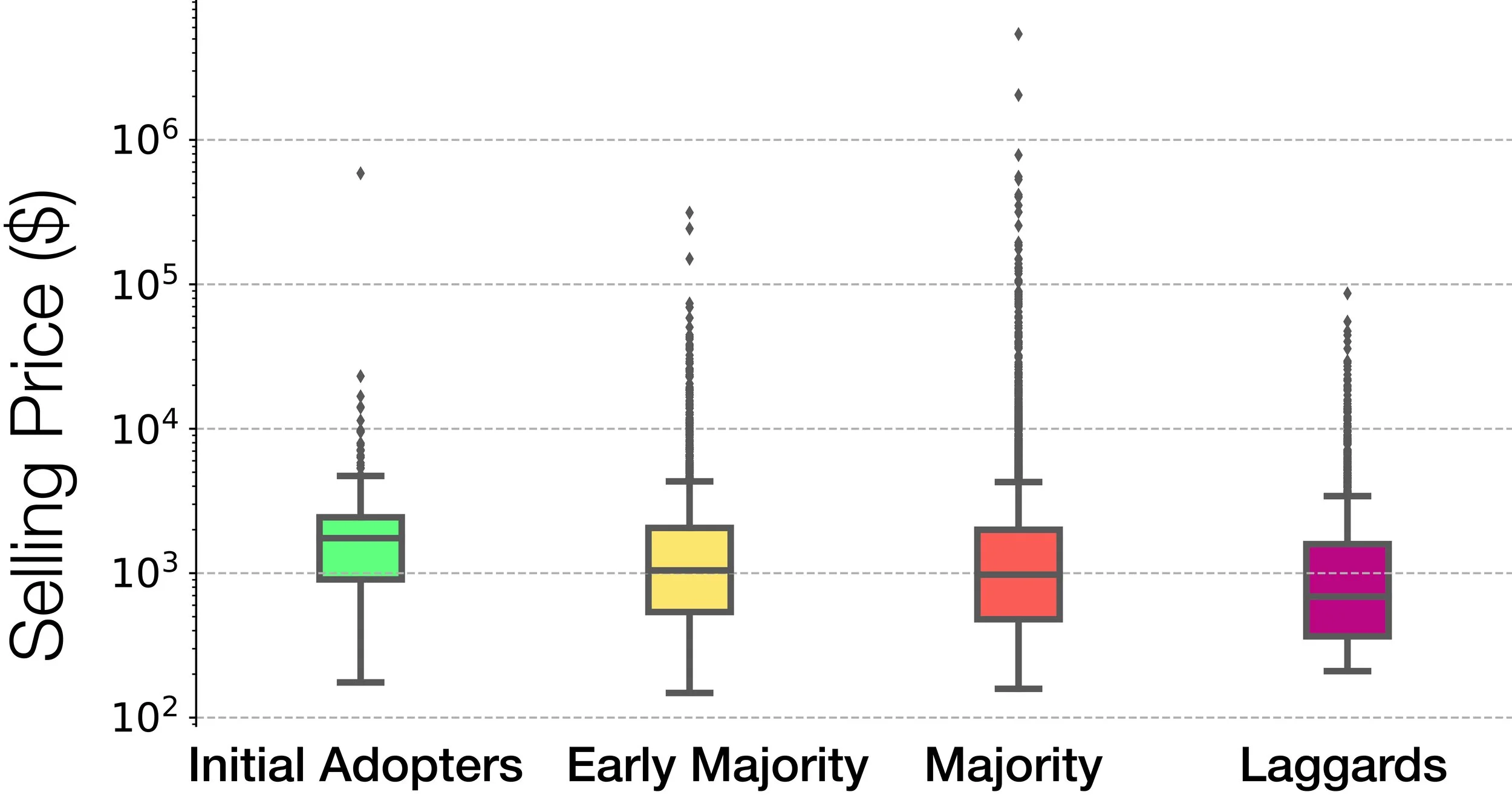

Selling prices of Foundation artists segmented by the period during which they joined the platform, showing a first-mover advantage between groups. Courtesy of Barabási Lab.

Artists who joined Foundation earlier sold more NFTs on average, and at a higher average price per NFT, compared to their counterparts who arrived later in the platform’s life cycle. This led the early entrants to higher total earnings overall. Barabási and company wrote that these results reflected a clear and lasting “first-mover advantage” in terms of artistic success.

Notably, the researchers found that the first-mover advantage applied to more than just the very fastest artists off the starting block. The effect persisted even when comparing different groups of artists that joined Foundation at different junctures to one another.

Yes, the group labeled the “initial adopters”—the first 2.5 percent of artists to start on Foundation, joining between January 21 and February 22—out-earned the “early majority” artists—the 13.5 percent of artists who joined between February 23 and March 10. But the early majority, in turn, also out-earned the later “majority,” who in turn out-earned the “laggards,” the 16 percent of artists who began selling on Foundation between May 19 and the study’s conclusion.

We can see the effect more clearly by breaking it down into components. Of all NFTs offered on Foundation during the initial-adopter period, more than 74 percent found buyers. Yet the same was true for a smaller and smaller share of the NFTs released during each subsequent phase of the market, ending with only about 13 percent of the NFTs offered in the laggard phase selling.

A similar relationship manifested in terms of NFT sale prices (shown in the chart above). The median selling price (meaning, the price separating the top half of results from the bottom half) was $1,746 during the initial-adopter window. It dropped to about $1,046 during the early-majority period, however, before sinking to about $976 during the majority phase, and $688 during the laggard phase.

What accounts for the first-mover advantage? Barabási and his team chalk it up to two related factors. The first is what I’ve previously called the “tyranny of options“: as more and more people offered more and more works on Foundation, artists naturally had a more and more difficult time standing out. Second, the initial frenzy to get in on the NFT market subsided over time (presumably as Beeplemania ebbed), leading buyers to pull back on their purchasing. In short, both supply and demand favored the early adopters.

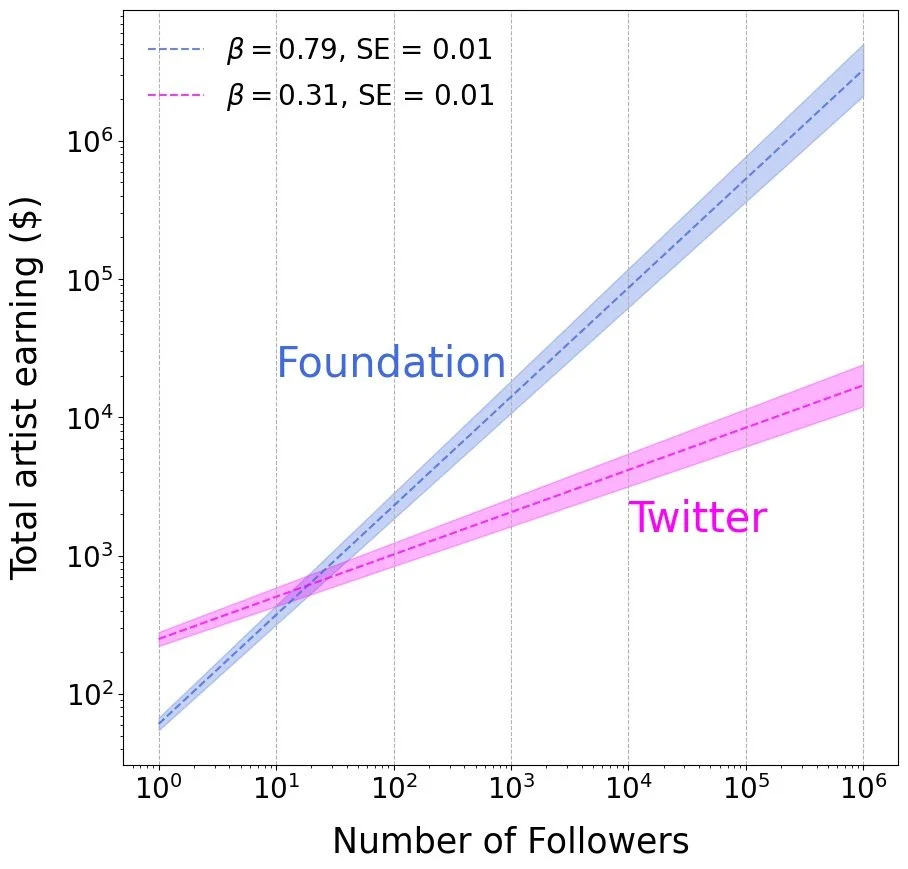

Earnings of Foundation artists in relation to follower count on Foundation versus Twitter, showing the former is exponentially more important to sales than the latter. Courtesy of Barabási Lab.

Like Twitter or Instagram, Foundation allows users to follow artists on its platform to receive notifications about their activity, including new NFT drops. Yet Foundation is only a niche within a niche of the crypto space compared to Twitter itself, which has become the headquarters of crypto enthusiasts in general and crypto artists in particular.

This is part of the reason why NFTs are often seen as a mechanism for monetizing viral fame. Think of the NFTs for the original Nyan Cat GIF and Disaster Girl photo selling for almost $600,000 and $500,000, respectively. It’s difficult to imagine those prices (and many others) soaring so high in the crypto space without the consensus-building propulsion of Twitter. No wonder many, if not most, artists tweet about their Foundation drops to maximize visibility and (they hope) prices.

But the data shows that this cross-platform marketing strategy provided mixed returns. Gaining Twitter followers modestly boosted artists’ sales; gaining Foundation followers dramatically boosted artists’ sales.

By growing their Foundation audience from 100 followers to 1,000 followers, the study found, artists “likely experience a tenfold increase in earnings.” Artists would have to increase their Twitter follower count from about 100 to 10,000—an order of magnitude more—to capture an equivalent rise in earnings.

The analysis suggests that Foundation is something of a closed circuit for crypto artists. Their online presence elsewhere is nice—but unless they can port their audience over to Foundation, their success there will be limited.

Network map of the 204 artist clusters that emerged during Foundation’s first 100 days, showing which artists invited which others onto the platform. The 20 largest clusters by quantity of artists are each displayed in a different color, with each node corresponding to a single artist, and the size of each node corresponding to that artist’s sales volume. Courtesy of Barabási Lab.

As a so-called “open” platform, Foundation grows its creative community by allowing artists to invite other artists to show and sell there. This dynamic hews closer to the utopian, collectivist rhetoric of crypto than closed platforms like SuperRare, which grows by “onboarding only a small number of hand-picked artists,” according to its website.

Since every Foundation artist’s profile page includes an “invited by” tag, Barabási and his team were able to map every network of invitations that sprouted on the platform in its first five months. They found that the 14,706 artists who were on board by mid-June arrived via 640 individual networks (which the researchers call “artist clusters”), each made up of an average of 22 artists.

Crucially, the data showed that select artist clusters dramatically outperformed others. The chart above shows every one of the 204 artist clusters that emerged in Foundation’s first 100 days, with the top 20 clusters by number of artists each displayed in a different color. (For an animation representing their growth over this time span, click here.)

Based on these results, Barabási and company were able to separate the sell side into what they called “rich” and “poor” artist clusters. The highest-earning cluster in the sample sold more than $2.7 million worth of NFTs, with a mean price of nearly $6,800 per token. Both measures eclipsed the maximum figures achieved by a randomized sample, where the highest-earning cluster sold only about $902,000 worth of NFTs, with a mean price under $2,700. (The effect persisted even after the researchers omitted the top-selling NFT in each cluster.)

The opposite manifested on the low end of the earnings continuum. The poorest artist clusters sold significantly less work by value overall, and at a significantly lower average price per NFT, than the worst-performing cluster in a randomized reference. So if you were offered a Foundation invite from an artist you knew to be struggling on the platform today (well after the first-mover advantage has disappeared), the data indicates you would be better off holding out for the prospect of a better offer later on.

Members of these extreme clusters were rich or poor in terms of more than just total earnings, too. They also sold significantly more (or less) NFTs by volume, had larger (or smaller) Foundation followings, and larger (or smaller) Twitter followings than randomness would allow.

Among these myriad metrics of success, then, the message was the same: new artists did about as well, or as poorly, on Foundation as whoever brought them on in the first place. So while the open platform democratized access, success was largely predetermined by artists’ pre-existing relationships.

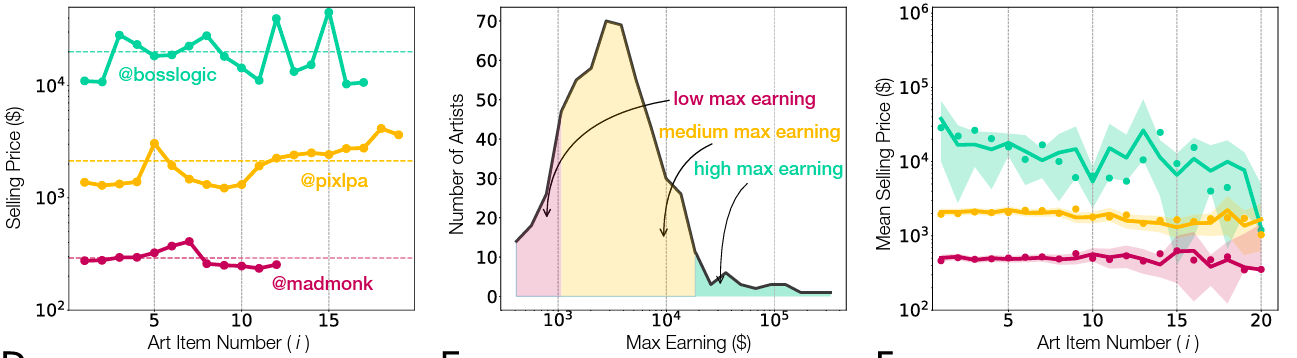

Segmentation of individuals artists’ prices (left), max earnings by group (middle), and mean selling price by group (right) based on their initial reputation. Courtesy of Barabási Lab.

On Foundation, artists are responsible for setting their own prices. In fact, if a new work fails to attract interest at its initial asking price, the artist can simply re-list it at a lower price to try to spur bids. (Foundation allows works to be offered for private sale or public auction; in the latter case, a 24-hour countdown clock begins when a bidder agrees to meet the listed reserve price.)

This setup means artists’ sale prices on Foundation theoretically could be much more responsive to demand than in the traditional gallery sector. There, dealers try hard to ensure that prices neither rise unsustainably quickly, nor fall too much, ever (even in the absence of demand).

On Foundation, however, each artist’s selling prices behaved like something of a hybrid: they often varied significantly from NFT to NFT—but they also tended to remain within a stable, clearly bounded range. Crucially, this range tends to be set by an artist’s very first sale. Informed by their findings about artist clusters and the sales significance of social networks, Barabási and his co-authors conclude that this price stability depends on an artist’s initial reputation.

The researchers used sales data to split Foundation’s artist population into three distinct classes (visible in the middle chart above, for max earnings): low-reputation (the bottom 20 percent of artists, all with their top sale coming in below $1,254), medium-reputation (the middle 75 percent of artists, all with their priciest sale falling between $1,254 and $18,510), and high-reputation (the top five percent of artists, all with their priciest sale surpassing $18,510).

To ground this discussion in specifics, consider the high-reputation artist known as bosslogic. Nearly all of the 17 NFTs that bosslogic sold on Foundation during the sample period traded for between $10,000 and $30,000 each. But individual prices rose and fell significantly within this price band. For instance, bosslogic’s eighth NFT sold for just shy of $28,000. Their next three NFTs went for between $11,000 and $18,200 each, before bidding pushed their twelfth sale to an outlier price of $39,708.

The same basic phenomenon played out among lower-reputation tiers of creators. For example, the artist known as pixlpa sold 19 total NFTs, each for between about $1,000 and $2,000. Those results cemented pixlpa in Foundation’s middle class of artists—significantly less successful than bosslogic and their high-reputation peers, but significantly more successful than low-reputation artists like madmonk, whose 12 sales generally closed at prices between $250 and $350 each.

The key finding is that the level of reputation impacts multiple measurable factors of success such as work-to-work selling price, mean sale price, number of NFTs sold, and maximum earnings, all of which mutually reinforce. The result is a kind of crypto predestination: in general, an artist’s odds of success on Foundation are set before they even mint their first NFT.

Comparison of nine artists’ offerings, sales volume, bidder counts, and collector counts based on earnings level. Visualization by Barabási Lab. Courtesy of Barabási Lab.

Among high-, medium-, and low-reputation artists, the sales data diverged and converged in important ways.

All three groups exhibited a direct relationship between sales growth and growth in the number of bidders; the difference was that high-reputation artists attracted new bidders at twice the rate of medium- and low-reputation artists.

But there’s a twist: what remained “indistinguishable” among the three groups, Barabási and company found, was the rate at which the three groups of artists found new buyers.

In other words, even as high-earning artists sold more NFTs and attracted new bidders faster than everyone else, their collector base grew no faster. More people were competing for their work than for the lower-reputation groups, but about the same amount were actually winning those competitions (relative to comparable points in each group’s sales history).

This means that new works by high-reputation artists tended to be acquired over and over again by a few passionate collectors, often at outsize prices driven up by wider-spread bidding. Medium- and low-reputation artists, in contrast, tended to see their NFTs acquired at consistently lower prices among a more equally matched pool of buyers.

Drilling into the data clarifies the relationship. Among the 2,743 NFTs sold by the 180 top-earning artists with 10 or more transactions, about one-third were purchased by collectors who had previously bought work by the same artist. The roughly $4.5 million spent by these repeat investors made up more than 76 percent of the total sales value for this cohort ($5.9 million). The upshot? The minority of works acquired by top collectors sold for vastly more than the majority of works acquired by everyone else, even if we restrict our view to works made by a single artist.

The sales history of the artist PaulSnijder illustrates the point. During the study, nearly 62 percent of PaulSnijder’s earnings by value came from just six NFTs acquired by just three repeat collectors. Their other 21 sold works, each purchased by a different buyer, provided the remaining 38.5 percent of their earnings.

Since the beginning of the NFT markets’ surge more than a year ago, one of the central hopes has been that the technology’s disruptive potential and ethos of democratization would lead to more equitable results than the legacy art market. For the most part, Barabási and company’s research into Foundation douses those hopes in cold water.

True, the findings offer some good news. The first-mover advantage (Point #1) may have changed the careers of artists who were early to enter the field. The influence of follower count on sales success (Point #2) also reinforces that it is possible for crypto artists to organically grow a lasting career, fan by fan (if you focus on the right kind of fans).

However, the study’s takeaways about rich and poor artist clusters (#3), initial reputation (#4), and the importance of forming strong ties with a shallow pool of wealthy buyers (#5) will sound all too familiar to most veterans of the art establishment. In fact, they chime eerily well with Barabási’s findings in a 2018 study of the traditional art world, which determined that the trajectory of artists’ careers depended to an overwhelming extent on whether they began showing in “low initial prestige” or “high initial prestige” galleries and institutions. That die, too, was cast by the the strength of their relationships with other successful artists, wealthy buyers, and tastemakers.

In this sense, the early data on Foundation suggests that a high-quality social network is still the chief mechanism for advancement in crypto art. The most revolutionary aspect of NFTs is that they shift the responsibility for constructing such a network wholly onto the artist. Remember, a synonym for “gatekeepers” is “market makers.” To the extent that crypto eliminates the former, it also requires artists to become the latter by tirelessly advocating to boost their own standing. But if self-promotion isn’t foremost in an artist’s skill set, Barabási’s research indicates, then reputation might be even more confining in the crypto space than it is outside it.

A view of the Capitol rotunda in Washington, D.C. Photo: Matt H. Wade. Courtesy of Wikimedia via Creative Commons License.

This week, switching the focus from payouts to procedures…

Read More