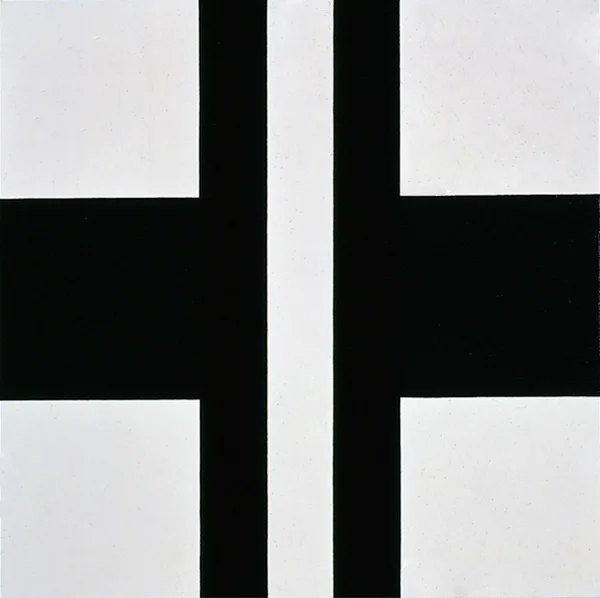

Divided We Fall

Repetition is a powerful thing. As Aristotle said, "We are what we continually do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit." Unfortunately, though, repetition can also be just as effective at limiting us. How often have we backed away from something new or challenging because we believe it's beyond our capabilities? How much more could we achieve if we stopped retreating to our trusty beliefs about our own flaws? And how much harder is it to break the cycle when not just an individual, but rather an entire industry, collectively buys into the same myth about what can and can't be done?

This Tony Robbins-esque train of thought chugged through my brain after I read M.H. Miller's ARTnews piece on the challenges facing recently appointed Pérez Art Museum Miami director Franklin Sirmans. Even apart from the lingering turmoil within the museum's board, rising competition from other contemporary arts-based nonprofits in Miami, and creeping anxiety about local philanthropists' funding capacity, Miller hoists an all-too-familiar red flag about Sirmans's future: "his reputation... is as a curator and critic, not a fundraiser."

Perhaps nothing else terrorizes the museum sphere like the perceived divide between "curator" and "fundraiser." As former MOCA director and tireless self-mythologist Jeffrey Deitch recently declared, "If you're a museum director... the majority of your time is spend fundraising... At [MOCA], it was 90 percent business, 10 percent art. It was just constant, endless fundraising." Importantly, Deitch invokes this divide as both a badge of honor and a connoisseur's justification for his brief, tumultuous tenure as director: He failed because he was far too committed to trying to Live the Art rather than make the deals. And as we all know, he couldn't possibly do both, right?

Surprising as it may sound at first, the perceived divide between art and commerce also cuts through the gallery sector to some extent. Many, if not most, sufficiently-sized galleries split their staff onto opposing banks. Instead of curator versus fundraiser, the roles most often become "sales associate" versus "artist liaison." The former deals with the gallery's collectors, trying to entice them to buy work. The latter deals with the gallery's talent, trying to understand their needs so the work can be finished for sale in the first place.

Now, in well-run and well-staffed galleries, the two sides of the organization communicate freely enough to consistently bridge the divide. But in galleries where the communication is sub-par (or worse), the divide threatens to engulf the whole enterprise. And even in the best cases, the disconnect between business and creativity is still hard-wired into the system for everyone to see: The people in charge of selling the work are not the same people in charge of relating to the artists. So surely, it must need to be this way, right?

I reject the premise. Regrettably, nonprofits and for-profits alike have invested serious intellectual capital in, essentially, keeping business and culture separate but equal. Worse, many have even gone so far as to structure their organizations around it. My concern is that, in doing so, they've made the divide between commerce and art––as well as the perils it sets up––a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Yes, it's rare to find people capable of excelling in both roles. But maybe that's partly because so many of us in the arts have sustained, even reinforced, what is basically an urban legend. ("Don't learn too much about business, or else the Chelsea Devil will eat up all your creativity!") In reality, some of the world's greatest artists, gallerists, and nonprofit directors have been their own best salesmen. After all, what else is selling (or fundraising) other than passionate advocacy, deep knowledge, and good storytelling about a cause one believes in?

That's why I would argue that very few people who bridged the gap did so accidentally. And that's also why I would encourage everyone in the industry to dismiss the hype and do the same. Divided, we fall into the same patterns, the same beliefs, the same self-imposed limitations. United, we––and the arts––stand to gain so much more.