The Shadow Knows

In every medium and every era, artists who want their work to connect with an audience have to continuously face three hard questions: What do the people want right now? How much ambition or innovation is too much for them? And when is less actually more?

I've been thinking about these puzzle pieces a lot since last week, when I read "The Shadow," Alex Ross's recent re-evaluation of Orson Welles in The New Yorker. As some readers may know, Welles's legacy has been a longtime battleground for critics. One camp argues that his artistry burned blindingly bright but flamed out early, plunging his career into awkward darkness after just a few groundbreaking stage plays, radio dramas, and films. Another camp argues that Welles's often star-crossed later work was actually so forward-thinking that we're only now able to appreciate its prescience and impact.

Central to this debate is the scale of Welles's ambition, especially as it relates to audiences both then and now. Near the end of the piece, Ross addresses that lingering question with the following lines:

If one Welles myth deserves to die, it is that he was a wasteful filmmaker. His career is, in fact, a sustained demonstration of the art of making something from nothing. It might be time to stop imagining what might have been and instead to focus on what remains... Making art is difficult, especially in a culture that has cooled on grand artistic ambitions. These tidy parables of rise and fall, of genius unrealized, may say more about latter-day America than they do about the ever-beleaguered, never-defeated Welles.

In other words, Ross argues that Welles was simply too ambitious for his own good. He either misread his audience, or he stopped caring whether they were ready for what he wanted to do. His fatal flaw paralleled that of Citizen Kane's titular tycoon, as he went so big and demanded so much of the world around him that he lost touch with people entirely.

That concept stuck with me. But the more I've turned it over in my head since reading "The Shadow," the more counter-examples have come to light for me.

Fittingly, it started with movies. Just last week––less than 24 hours after I absorbed Ross's piece, in fact––I took in a sold-out, limited engagement, three-hour-and-seven minute "roadshow" screening of Quentin Tarantino's The Hateful Eight, complete with an orchestral overture and intermission. As Tarantino has stated over and over again on his press tour for the movie, the whole concept is to reclaim true event status for movies rather than let the culture degrade them into throwaway entertainment. The early returns suggest his strategy succeeded.

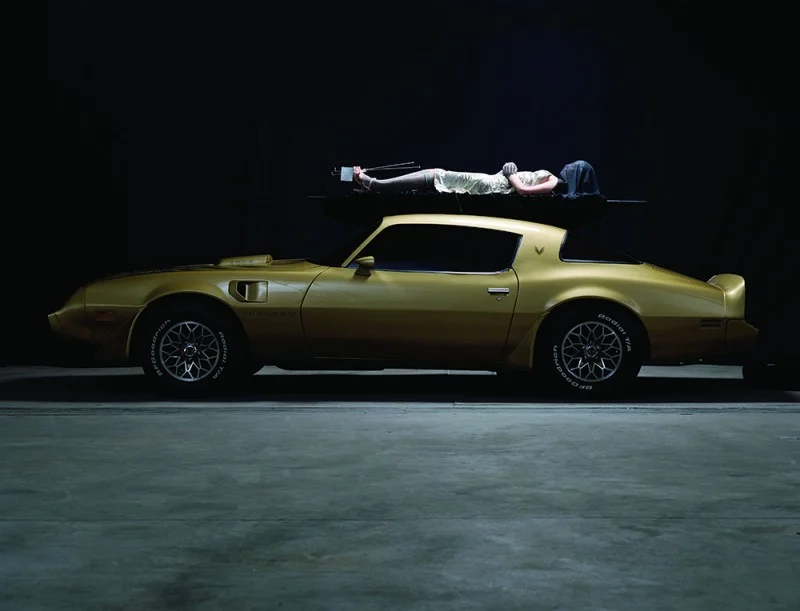

Thinking about movies and art more broadly then got me thinking about Matthew Barney. Since October, MOCA Los Angeles's headlining show has been his latest opus, River of Fundament: a three-part, nearly six-hour film and a series of related works that includes sculptures weighing up to 25 tons. (Side note: You can find my live-tweeted commentary of the film here.) Love him or hate him, Barney's grand ambitions have made him an enduring presence in the contemporary art conversation since the debut of his previous avant-garde extravaganza, The Cremaster Cycle, more than a decade ago. And River of Fundament suggests he sees no reason to reverse course now.

Nor is this phenomenon of grandiosity limited to filmmaking, either popular or art house. In 2014, unapologetic maximalist Jeff Koons's retrospective at The Whitney reportedly drew in well over a quarter-million visitors, shattering its revenue and attendance benchmarks by 176 percent, according to the exhibition's media strategist. Meanwhile, no art lover's summer in New York that same year was complete without a pilgrimage to Kara Walker's monumental installation A Subtlety: or The Marvelous Sugar Baby inside a former Domino sugar factory.

And just when I was ready to say that creative bombast might only be viable for big names with major institutional support, I remembered a Christmas Eve New York Times Art & Style section feature on The 14th Factory, a sprawling group exhibition of mostly unknown contemporary artists set to debut this April in Manhattan's disused 23 Wall Street building. Curated by UK-born, Hong Kong-based Simon Birch, the show will stretch across nearly 150,000 square feet thanks to an independently financed budget of $3 million.

The 14th Factory's ultimate success or failure is yet to be determined, of course, but the pure fact that it exists only sharpens the point knifing through the other examples: The evidence suggests that audiences have not, in fact, "cooled on grand artistic ambitions." In fact, I would argue that Ross has read the culture exactly backwards.

At the very least, his conclusions in "The Shadow" skate over an important distinction between mass audiences and niche audiences. It may be true that, much of the time, the former just wants to be entertained, and so they'll generally opt for content with only minor ambitions and soft demands. (My hunch is that this thinking helps power the general 21st-century preference for TV series over movies, for instance.)

But the evidence suggests that the latter group––the smaller but more passionate minority––now wants the polar opposite. They crave the ambitious and epic, if not always the challenging and innovative. They lust for art that transcends expected standards and becomes an EXPERIENCE (or at least tries to).

This possibility is especially crucial to contemporary art, which is by its nature a niche medium rather than a mass medium (as I've written before). The people actually buying artwork, and even simply paying to see it, still only make up a small, dedicated subset of the general population. And yet at the same time, the Koons retrospective illustrates that that niche may be larger than ever before––and still growing.

Artists hoping to build or sustain their careers would do well to recognize this trend, whether they're as established as Koons and Barney or as unknown as Birch and his 14th Factory collaborators. I suspect that Welles would have been pleased by their examples. Because just as in the classic radio show, when it comes to what audiences want, The Shadow still knows.