Not a Businessman, But a Business, Man

One of the most difficult, yet most valuable, lessons I've ever learned is that you don't always get to decide what you are to other people. For example, I still remember realizing in my first year of college that I would never be considered an ice-cold, chrome-smooth, James Bond-type man's man. It just wasn't my nature, and I was only knee-capping myself by trying to make the world see me that way. When I started to embrace what I thought were my genuine positive traits––regardless of how they exploded my chances at the 007 ideal––things got better.

This same hard but important truth applies to the professional realm, especially for fine artists. Yes, acknowledging your nature is crucial to unearthing a compelling style, approach, and narrative. But despite the myth of the artist as enlightened seeker kicking herself free of the corporate world, it's just as crucial to accept that, like it or not, unavoidable parts of civil society will still view artists' all-consuming quests as one thing and one thing only: a business.

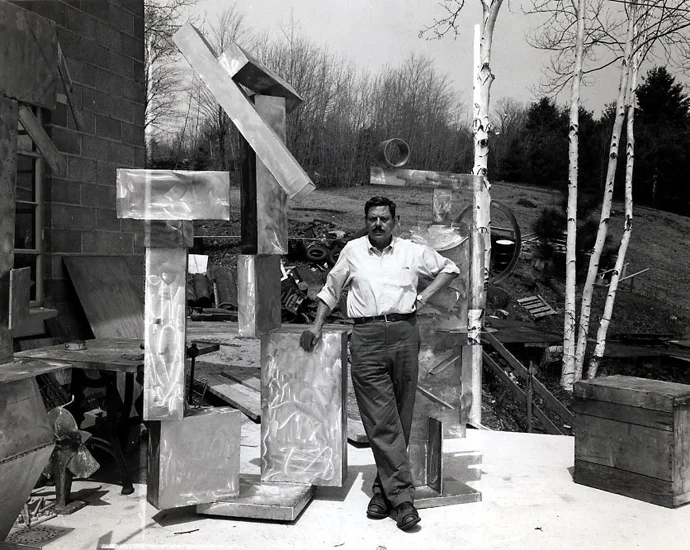

I started thinking about this angle after reading fine-art attorney Ronald D. Spencer's recent deep dive on why courts tend to drastically overvalue the works left behind in artists' estates. Spencer explores the depths of the issue via rulings in cases involving three 20th-century blue-chip legends: David Smith, Georgia O'Keeffe, and Alexander Calder. And while there are valuable insights in each of Spencer's analyses, it's his take on the Smith case that sent me back to my keyboard this time.

The dispute in the Smith case centered on the appropriate tax valuation of the 425 sculptures orphaned by their maker's death in a 1965 car accident. Assuming one-by-one sales to various buyers in a vacuum, the executors of Smith's estate estimated a total "retail value" for the works of $4,284,000. However, given that Smith's passing effectively thrust all 425 pieces onto the market at the same time, the executors' also took the position that their own retail estimate substantially overvalued what the market would actually bear.

To resolve the discrepancy, the executors argued that the works' tax value should be determined by cutting the retail value with what's known as a "block discount." Broadly speaking, a block discount is a price reduction applied to a pool of assets' to account for their bulk sale. The idea here is that the sudden and very real oversupply of Smith works on the market would restrict the actual potential buyers to, in Spencer's words, "a person or syndicate acquiring the sculptures for future resale"––a major up-front investment that he rightly assumes would require 10 years or more to return a reasonable profit. This "person or syndicate" would undoubtedly price these business drawbacks into their offer, thereby lowering the estate's potential payout below the $4,284,000 retail estimate.

How far below? The executors proposed a 75 percent block discount, then hacked away another 33 percent from the subtotal to account for the sales commission owed to Smith's primary gallery, Marlborough Fine Art. Through this calculus, the sculptures' "date-of-death" tax exposure would drop to just $714,000.

Unfortunately for Smith's estate, the court rejected this line of thinking. Its 1972 ruling took a middle road on the issue of block sale: The oversupply issue should be taken into account, but the sales would still ultimately behave more like retail transactions than a bulk exodus. Furthermore, the court denied the entire idea that Marlborough's commission should be factored into the works' tax valuation. Combining these factors led it to approve a block discount of only 33 percent, saddling Smith's estate with a tax burden of $2.7 million.

With 44 years of hindsight, Spencer disagrees with the court's ruling. And his rationale crystallizes the notion that, in the eyes of the law, creating artwork is a business like any other (emphasis mine):

Instead of trying to determine what each retail buyer would pay for a given sculpture, the Smith Court should have determined what a hypothetical estate buyer would have paid, since an estate bulk buyer would necessarily have made his own calculation for future retail (and wholesale) sales. The point becomes more clear, if one thinks of the sale by the Smith estate of the art inventory of David Smith's “art business." Accepted procedures for selling a business owned by an estate clearly suggest that the estate executors would not seek to sell inventory into retail market. Rather, the executors would seek out a bulk inventory buyer interested in investment and future resale in retail and wholesale markets, who would also consider his selling expenses.

Now, I've encouraged artists to think of themselves as small businesses before––first here, and more recently here. I'd even call that idea a vital organ in my body of opinion about how to function in the industry. But while I can name a variety of proactive arguments for adopting that mentality, Spencer's piece provides an equally important reactive one. Whether or not artists want to consider themselves businesses, that's precisely how law-makers, law-interpreters, and law-enforcers will treat them anyway.

So, to every artist reading this post: If you'll allow me to paraphrase Jay Z, you're not a businessman. But you are a business, man. The sooner you come to peace with that fact, let alone embrace it, the better equipped you'll be to defend the unique livelihood you're pursuing.