Advertorial: On Public Art vs. #SponCon, the MCA's New Ad Campaign + Italy's Nationalist Art

This week, stories about the fog-dense borderland between art and publicity…

PAYING PEANUTS

On Monday, Andrew R. Chow of The New York Times informed us that Peanuts Worldwide, the media company that manages the licensing and use of cartoonist Charles Schulz’s beloved creations, has commissioned seven contemporary artists to reinterpret Charlie Brown and friends in a series of murals in major cities worldwide.

Dubbed the Peanuts Global Artist Collective (seriously), the group consists of individual high-art luminaries (Kenny Scharf, Rob Pruitt, Nina Chanel Abney), emerging talents (painter Tomokazu Matsuyama and street artist André Saraiva), and buzzy collaborative entities (AVAF and FriendsWithYou—amusingly, collectives now temporarily operating inside another collective).

The end result will be multiple murals, each sized roughly 10 feet high by 15 feet wide, filtering the Peanuts crew through the seven artists’ respective aesthetics. The works will premiere on the exteriors of a group of office buildings in New York’s Hudson Square on April 16 and stay on view for three months. “Similar projects” will appear in San Francisco, Mexico City, Paris, Berlin, Seoul, and Tokyo, according to Chow.

While the whole “Peanuts Global Artist Collective” moniker is a little over the top, I’m heartened by the fact that I didn’t see anyone in the art world lose their minds over this announcement last week. It’s not the fall of Rome for seven non-superstar artists to cash what I presume is a nice check for a kinda fun project that hurts no one. And frankly, I feel pretty confident that if you ever start sharpening your sword to go to war against Snoopy, it might be time to step back and reflect on your priorities.

At the same time, it’s fair to ask whether these murals really qualify as a “public art project”—the term Chow uses to introduce the murals in the story’s lede. Yes, each of those three individual words applies to the Peanuts murals in isolation. To me, though, the spirit of public art implies a level of disengagement from the work’s funding source, and it’s hard to find any such disengagement here.

As a counter-example, consider Deborah Kass’s crowd-pleasing OY/YO, still on view in Brooklyn Bridge Park. There, Kass was commissioned by real estate management firm Two Trees to produce a public sculpture for a specific green space. But it’s not as if Kass had to contour the void in the ‘O’ so that it became the company’s logo.

Now let’s jump back to the murals, which simply re-broadcast characters owned by Peanuts Worldwide through a jazzy high-art filter. Charlie Brown and the gang may be whimsical cartoons, but they’re also intellectual property that generates tangible and intangible products worth a fortune. Consider that last year DHX Media acquired Schulz’s Peanuts and Strawberry Shortcake for a cool $345 million. No wonder reading from top to bottom of the official Peanuts FAQ takes you on this wild ride to the corporate side:

- CHARACTERS: Does Charlie Brown have a girlfriend?

- COLLECTORS’ ITEMS: What’s the value of a particular Peanuts product?

- SPECIAL REQUESTS: As a Peanuts fan, I often come across content on the internet that uses the PEANUTS copyrights and trademarks in an unfavorable fashion, and I don’t think it is authorized by PEANUTS Worldwide. What actions does PEANUTS Worldwide take to protect the work of Charles Schulz and the PEANUTS property?

Again, I don’t begrudge any members of the Peanuts Global Artist Collective for capitalizing on this opportunity. Pruitt, for one, is quoted in a statement as saying he thinks he taught himself to draw by tracing Peanuts characters. It’s cool to get to professionally engage with something you grew up loving, especially if doing so can also help fund other, more avant-garde projects.

Let’s just be clear-eyed about the boundary between public art and #SponCon (also known as “sponsored content”) when we’re discussing projects like these. I think it can be legitimate, maybe even a little subversive, for artists to accept some corporate cash if they funnel it into serious work that refuses to blatantly advance the patron’s agenda. But if you’re trying to distinguish between good art and creative advertising, remember that the visuals themselves usually give us a solid indication of who’s co-opting who.

AD AGE

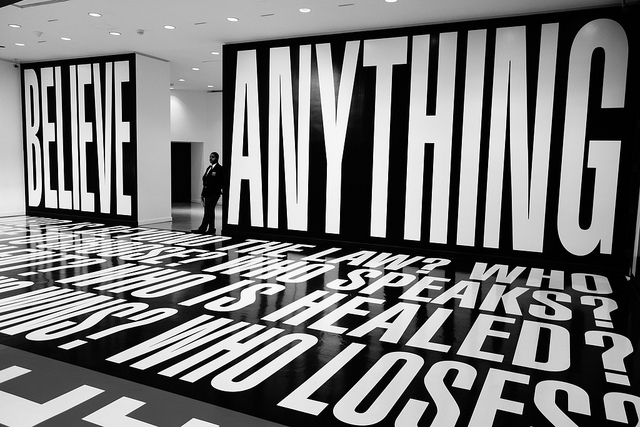

Last Saturday, ArtDaily relayed that Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) had embarked on its “first major advertising campaign… in 20 years.” Titled “Made You Look,” the initiative is described as “a fully integrated campaign that leverages immersive storytelling across digital, social, and print to re-introduce the MCA to new and returning visitors” after the completion of the museum’s architectural redesign.

One of the campaign’s initial salvos was the Pindell Pop-Up Experience, “a blend of art, music, fashion, and fun centered around the pivotal year 1979”—and, you know, also the work of Howardena Pindell, whose first survey exhibition the MCA hosts until May 20. Presented in a storefront inside Chicago’s bougie Wicker Park neighborhood, the pop-up—which closed on Sunday evening—included, according to the press materials:

Augmented reality viewfinders, throwback video games such as Space Invaders, a record vinyl wall, a Walkman listening station, and a Pindell-inspired wall mural made for selfies. Visitors [could] also read through comics and magazines from the 1970s, and get a complimentary screen-printed T-shirt with legendary quotes from Howardena Pindell that are still relevant today.

Now, when I first read this description, I’ll admit that I felt a little queasy. But in fairness, part of that may have been due to the flashbacks it triggered to my wilderness years ghostwriting for commercial directors—an era where I regularly listened to conference calls featuring ad executives pimping these same kinds of ideas for everything from beers to cleaning products to diapers. (Example: “Imagine a beautifully welcoming, cushy-soft room that makes visitors feel like they’re INSIDE THE HUGGIES.”)

But there’s a crucial counterpoint here. As I wrote earlier this year vis-à-vis Newfields director Charles Venable and his argument for transmogrifying Indianapolis’s premier art museum into a kind of free-wheeling cultural playground:

Philosophically, Venable’s argument boils down to this: The traditional museum model no longer works in the age of the attention economy. Art institutions now have to compete with everything from music festivals to farm-to-table restaurants to, maybe most of all, the endless smartphone notifications yanking us around with the insistence of a kid who chugged two liters of soda with no awareness of the route to the nearest bathroom.

The Pindell Pop-Up Experience represents an offshoot of this same idea—and, like it or not, a pretty savvy one, in my view. Think of it as the institutional equivalent to the persona most of us conjure on a first date (or any social media platform): strictly the most fun version of something much more complicated and challenging. There’s a world-wary logic to all of the above. Without being disingenuous, you do what’s necessary in the current climate to get people in front of you, and then you try to hook them on the real thing beneath the lighthearted exterior.

The reality is that it’s a battlefield out there. Arts institutions are fighting for their lives in a multi-front war where Peanuts Worldwide is commissioning contemporary artists, the Yankee Candle brand is staging “immersive installations,” and the Museum of Ice Cream is bringing in audiences larger than some blockbuster exhibitions. So if your gag reflex triggers at the thought of the MCA and an ad agency let’s say, “distilling” Howardena Pindell into a tasty weekend spritzer of arcade games, colorful selfies, and #woke t-shirts in the hope that it will lead to serious engagement with her work and legacy, don’t hate the player. Hate the game.

[ArtDaily]

ILLIBERAL ARTS

Finally this week, Hannah McGivern of The Art Newspaper unpacked the surprising news that Matteo Salvini, the ringmaster of Italy’s newly empowered far-right La Lega party, has proposed grandiose measures to champion the arts as a tool for nationalist glory. Within his sweeping political manifesto, Salvini includes three pages on “cultural heritage and Italian identity” in which he throws his support behind “the creation of the largest museum of Modern art, architecture, and design in northern Italy,” along with other initiatives on the nonprofit and for-profit sides alike.

McGivern reports that La Lega “did not respond to [TAN’s] queries about the proposed museum, and its manifesto does not include details of what would actually go on display there.” But we do know that most of the proposed collection would be housed in a building known today as Palazzo Terragni, a former Fascist headquarters converted after the war into offices for some of Italy’s financial enforcement officials.

As for Salvini’s vision for the arts beyond the new museum, McGivern relays that the manifesto also pitches establishing a “centralized marketing department to drive cultural tourism in tandem with regional authorities and the 30 major state museums,” as well as reducing VAT for art acquisitions while dialing back what the document terms “excessive public control” of the antiquities trade.

All of this, in Salvini’s mind, will maximize “the strategic asset of our country” and strengthen “the industry that can guarantee [Italy] primacy compared with the rest of the world.”

Jarring as it seems for the far right to bolster, not ignore or attack, the arts in 2018, we’ve been here before. Remember, the only significant Modernist movement in Italy, the Futurists, openly pledged allegiance to fascism. Led by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the group’s work sought to glorify the Italian war machine at every turn and assumed they would become the regime’s cultural standard-bearers once Italy and its allies emerged victorious. And if it were released today, just imagine which contemporary online media outlets might be eager to run Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto—a screed that includes within its program the declaration, “We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism, and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.”

But it’s even more important to keep in mind that the Futurists were not exactly a historical outlier, at least in the broad sense. Think of how much artwork the Catholic church commissioned to promote the Crusades, or how much Hollywood fare the US military has helped produce since filmmaking’s American debut. This tactic is not new.

Neither is it partisan or denominational. Although many of us like to imagine cultural patronage as the sacred ground of the left, La Lega’s proposals serve as a vivid reminder that the arts can be commandeered to advertise sociopolitical causes anywhere on the spectrum. We all know that history repeats itself, or at least rhymes. So let’s also keep our eyes on the fact that art history is almost never separate from that grander arc—and that it can be made into a weapon as easily as it can be made into a salve.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: Sometimes you try to sell the art to other people, and sometimes the art tries to sell something else to you.