Why the Art Market’s Pivot to Asia Is About More Than Chasing New Wealth

This week, a reminder that bigger is not always better…

THE WAY FORWARD IS EAST

Last week, a trio of high-powered former Sotheby’s execs formed the second important new art-business alliance to openly prioritize Asia over longer-standing havens of collector wealth. However, a broader look at data on wealth accumulation reinforces that more factors are driving this strategy than a simple survey of where money is piling up fastest. An informed insider’s perspective confirms that this is another situation where the art market is evolving by rules that even an informed outsider would never suspect.

The latest headline-snatching team-up is Art Intelligence Global (AIG), the firm formed by Amy Cappellazzo, ex-chair of Sotheby’s fine art division; Yuki Terase, Sotheby’s former head of contemporary art in Asia; and Adam Chinn, Sotheby’s ex-COO. The troika announced the partnership via a New York Times piece published last Wednesday, maximizing their odds of becoming (however briefly) the talk of VIP day at Frieze London and Frieze Masters.

AIG’s mission is to be a 360-degree advisory firm with a special focus on serving Asia, according to its three partners. The business will span two locations: one in Hong Kong captained by Terase and featuring “a large exhibition space,” and another manned by Cappellazzo and Chinn in the old Pace/MacGill building on East 57th Street in New York. (Cappellazzo and Chinn, who will manage legal and business affairs while staying on in his role as co-chair of anonymity-privileging online-sales platform LiveArt, are slated to work remotely until the latter space is ready next year.)

This approach chimes with some of what we heard in August, when the Times also served as the public launchpad for LGDR, the nascent consortium of high-flying dealers Dominique Lévy, Brett Gorvy, Amalia Dayan, and Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn that will officially debut next year. The quartet will provide a full slate of services for the global art market, with each partner leaning into a different area of expertise. However, the most talked-about plank in LGDR’s platform has proven to be its pledge to participate only in art fairs in Asia, “where fairs remain an important gateway to a wider array of young collectors,” in the words of the Times‘s Robin Pogrebin.

I doubt I need to remind you of the justified narrative about East and Southeast Asia’s growing importance to the art trade, particularly the market for living artists. A $185 million sales cycle at Sotheby’s Hong Kong this October stands as only the latest evidence of the region’s ascent, which has been boosted further and further since 2013 by the arrival of Art Basel Hong Kong (though homegrown Asian fairs are doing more than fine, thanks very much) and a seemingly ever-expanding brigade of buzzy blue-chip Western dealers parachuting into permanent spaces across the continent.

In AIG’s case, the driving force for prioritizing Asia seems to be that the partners see the continent’s burgeoning collectors as having substantially higher upside than top Western clients. Cappellazzo told the Times that major U.S. collectors “have so much already that they are only buying to fill in.” In comparison, the rapidly growing population of Asian buyers tends to be much more active “because they’re starting to build something.”

Based on all this, you might think that global wealth trends point squarely toward Asia being the nucleus of top-end wealth creation both today and tomorrow. But it turns out the data isn’t so one-sided. In fact, at least one recent study by a major financial institution found that the millionaire and billionaire class in Asia is actually growing much more slowly than in North America—and may continue to do so for years to come, seemingly complicating the narrative of unrivaled opportunities in the Eastern market.

FIGURES OF INTEREST

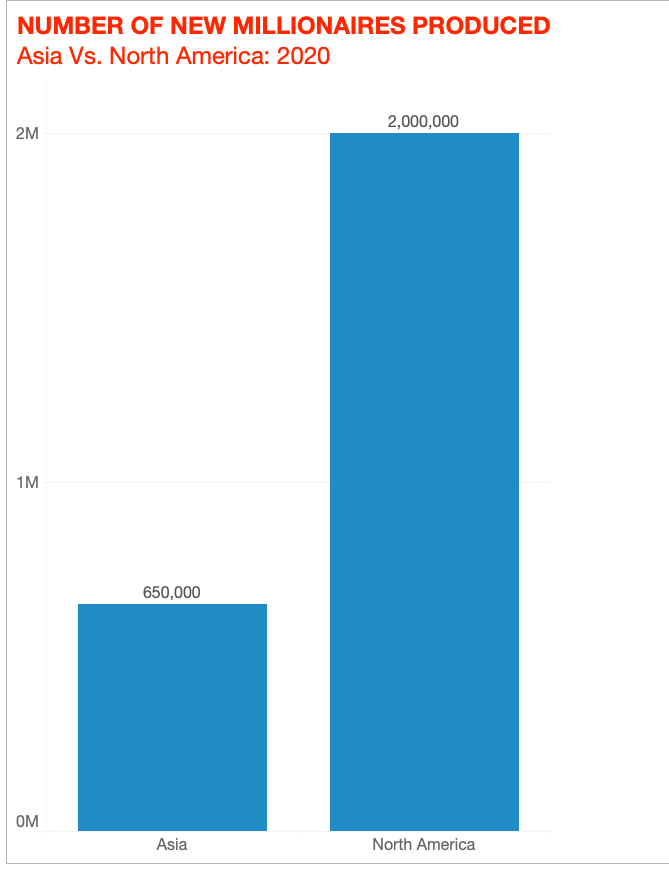

Released this June, Credit Suisse’s latest Global Wealth Report defied several of my expectations about the rates at which riches are accumulating in different regions. The study estimated that in 2020, North America added about three times as many new “dollar millionaires” (2 million) as Asia (650,000). It also found that the U.S. alone added about 70 percent more new ultra high net worth individuals (UHNWIs) than the top nations in Asia: 21,300 U.S. UHNWI versus about 12,400 Asian UHNWI.

(The report defines “dollar millionaires” as individuals whose financial and non-financial assets, including the value of their homes, add up to a net worth of at least 1 million U.S. dollars, and UHNWI as individuals whose net worth exceeds $50 million by the same considerations.)

Credit Suisse’s outlook for the future tilted in Asia’s favor to some extent, though not decisively. The bank’s quants projected that, by 2025, Asia will increase its dollar-millionaire population more than North America, but only by about 15 percent (8.8 million in Asia versus 7.6 million in North America). Even more surprising to me, the authors estimated that Asia will only add about two-thirds as many new UHNWIs (42,000) as North America (60,000) over the same period.

In other words, Asia’s populations of millionaires and UHNWIs are increasing at among the fastest rates on earth. It’s just that they are still being left in the dust by their counterparts in North America, especially in the U.S. The projections suggest that this won’t change in the next half-decade, either, at least when it comes to the very highest earners that AIG, LGDR, and their art-market competitors should be most eager to solidify relationships with.

To be clear, none of this is evidence to me that AIG and LGDR are making some kind of mistake by concentrating their resources on Asia in the ways they’ve outlined so far. However, after combining their strategies with the top-line figures in Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Report, it’s even clearer these heavy-hitters must view budding Asian millionaires and UHNWIs as more valuable on average than budding North American millionaires and UHNWIs, both now and later. Otherwise, what sense would it make to focus their energies anywhere other than what still is—and in some sense looks poised to remain—the most target-rich region on the planet (in both senses of the word “rich”)?

Still, this conclusion seems to contradict basic economic logic if you look only at the raw numbers. And when smart art-market actors with plenty of resources make moves like this, it almost always means there is more to their motivations than quants and outsiders would be able to intuit from the numbers alone.

AN INSIDER’S VIEW

To tease out a better sense of what’s happening here, I spoke to Brett Gorvy of Lévy Gorvy (and, of course, his prior post as Christie’s chair of postwar and contemporary art). Gorvy, who will apply his deep expertise in the Asian market to LGDR in the coming months, began our conversation by backing the now-popular notions that Asia is such a tantalizing market because of the youth and expansive taste of its burgeoning wealth, particularly the taste for Western art made within the last three years. Both the substantial investment in global online-sales infrastructure during the 2020 shutdowns, and the necessity to use it, have also been instrumental in expanding access for eager buyers in the region.

However, his most interesting point fits snugly with the wealth-accumulation data above in a counterintuitive way. Essentially, he argued that having fewer potential buyers to work with at present is actually an advantage for art sellers. That might seem like an odd position at first glance, yet it makes sneaky sense when you consider the wider social and institutional context in the region.

Take Hong Kong as an example. In the past, Gorvy said, Art Basel Hong Kong was one of the only worldwide fairs that consistently sold out its tickets. There was a “huge appetite from the local audience” because they had very few other options for exposure to art (again, particularly Western contemporary art) at scale. “The art fair becomes the access point for people to see multiple works by multiple artists and multiple dealers at one time,” Gorvy said, further clarifying LGDR’s interest in manning booths on just one continent.

The situation in Hong Kong has been slowly changing over the years. The homegrown museum scene is progressing, headlined by the (finally) soon-to-open M+ Museum. Again, both major Western dealers and major Western auction houses have been building out their presence in the city since the mid-2010s. But if you’re simply reading headlines and listening to conversations from afar, it’s easy to miss the colossal amount of work still to be done before Hong Kong’s art infrastructure rivals an older capital like London or New York.

The same is true on mainland China, as well as (to varying degrees) in nearby destinations like Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan. Despite so much activity in so many regional hotspots, Gorvy said, Asia’s art market “is still in its infancy.” This scenario offers galleries, auction houses, and advisory firms an almost unparalleled opportunity to educate the region’s art-curious about Western contemporary art even if they only establish one permanent base there—and as Gorvy put it, “education very quickly turns into buying.”

FORCE MULTIPLIERS

Asia’s education-to-buying pipeline is even more appealing to Western dealers because it’s small enough to get their arms around. For example, Sotheby’s recently announced that Asian bidders won 40 percent of the lots in its last four major evening sales across continents, as well as nine of the 20 priciest works the house sold in 2020. But when you break down the actual number of buyers in Asia bidding at the highest level, Gorvy said, “It’s still very small. You’re probably still talking about 30 to 40 people who can spend more than $10 million on an artwork, so that’s manageable in terms of outreach and the sense of community we all want to have.”

The modest size of the regional community also means that each prominent Asian art-buyer has outsized influence over the rest of the network compared to their equivalents in North America and Europe. A private collector like K Pop supernova T.O.P (Choi Seung-hyun) may have relatively more tastemaking power than an early-stage local art institution like M+, but both can much more aggressively impact which artists other Asian buyers target than, say, Beyoncé and LACMA can impact U.S. collectors, or Ed Sheeran and the Louis Vuitton Foundation can impact European ones.

Asian museums and foundations also magnify the continent’s market appeal because they are less encumbered by the traditional art-historical canon than their older Western counterparts. In Asia, Gorvy said, institutional collections are “being built from scratch. There is no historical collection. They’re buying the most contemporary works, the ‘now.’” This means it’s not unusual for a work by a living artist to be bought by an Asian museum for a major price at a London auction and “immediately be given prominence in the collection,” he said.

Compare that to what’s happening at a North American Goliath like MoMA, which is largely just recalibrating art history by adding more contributions from women artists or artists of color. It’s a fundamentally different institutional calculus with a fundamentally different connection to the market. Yes, a dead Western titan like Picasso can still be a gargantuan draw to Asian museum-goers. But Asian museums and foundations tend to prioritize exposing their large, art-hungry audiences to a higher concentration of Western artists who are freshly in-demand precisely because they have such better access to this cohort of artists than to established historical greats.

The Long Museum in Shanghai, for instance, has recently presented major solo exhibitions of Mark Bradford, George Condo, and Mary Corse, and it is set to open a Pat Steir retrospective this very week—the artist’s first major survey in China, according to the museum’s website. Incidentally, Lévy Gorvy showcased Steir’s work in a solo booth at Taipei Dangdai in 2020; Gorvy called the Long’s influence on the Asian collecting scene “a perfect example of when the platform exceeds itself.”

After absorbing these on-the-ground nuances of the Asian art market, then, it’s much clearer why LGDR, AIG, and a growing number of other Western art businesses see vastly more powerful incentives to pivot to Asia than an economist guided by global wealth data might.

Countries like China, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan may still be minting fewer millionaires and UHNWIs than in the U.S. However, less is more in the high-end art market in this case. The pool of high-income collectors has entered a Goldilocks zone for nimble Western firms: not too deep to overwhelm them, but not too shallow to warrant investment. Since each buyer in Asia’s still-compact community acts as a force-multiplier among their peers, even a relatively small firm can wield exponential influence in shaping taste in the region for the long haul, especially given the the well-documented youth and open-mindedness of so many of the region’s aspiring collectors.

So to me, the primary question is no longer why the Western contemporary-art industry is so eager to continue ramping up its Eastern infrastructure even as North America and Europe continue producing new fortunes; it’s only who will make a big move in Asia next.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: Even the most reliable data is only one piece of the puzzle.