Why ‘Global Weirding’ Makes Art Museums Needier Than Ever for Unglamorous Donations

This week, a story to chill the blood of any art aficionado...

THE COLD STAR STATE

Last Thursday, my colleague Brian Boucher surveyed the frigid plight that consumed Texas’s finest art museums after the state’s power grid proved unable to stand up to the most severe winter storm in memory. While the saga shined a cold light on a number of vital economic and political issues in Texas and the wider US, one has more relevance to the art world than all the rest: the urgent threat posed by climate change, particularly in a philanthropic environment that favors glamorous novelties over practical necessities.

First, though, let’s recap the basics. Glacial weather started blanketing Texas last Sunday, putting each of its 254 counties under a winter storm warning simultaneously for the first time in the state’s history. As Mother Nature tore down electrical lines, burst pipes, and inflicted Arctic temperatures on the land of the Lone Star (wild fact: CBS reported that the temperature in Dallas was at one point colder than in Anchorage, Alaska), residential and commercial power usage spiked to levels only “usually seen on 100-degree days,” according to the New York Times.

The unholy combination of meteorological damage, insufficient utility winterization, and unseasonable demand quickly overwhelmed Texas’s energy infrastructure, subjecting millions of residents to rolling blackouts that lasted for hours and, in some regions, even days. President Joe Biden issued a “major disaster declaration” for 77 of the state’s counties this past Saturday. By that point, the Washington Post reported, the storm had led to at least 500 deaths. Roughly 80,000 Texans were still without power and another 14.3 million were waiting for water service to return.

The state’s art institutions and arts workers did their best to endure the devastation. Here was Boucher’s summary of conditions:

While many people have been sitting in their cars with the heat blasting, museums have been relying on generators the size of small sedans in order to maintain the temperatures needed to properly protect artworks. Some employees have even taken refuge inside institutions like the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston in order to charge phones, warm up, and take advantage of functioning bathrooms.

Boucher relayed that, by Thursday, the MFA Houston had been largely reliant on backup generators for four days. Fortunately, on top of the relief it brought to staff, this contingency plan enabled the institution to keep its collection safely at “industry standards of 70 degrees Fahrenheit and about 50 percent relative humidity.” The museum reopened to the public on Saturday.

Yet not all of its peers were able to return to form so quickly. Although the Dallas Museum of Art and Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth also resumed normal operations this weekend, several of the state’s other institutions—including the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the Menil Collection, and the Blanton Museum of Art—announced that they would remain shuttered until at least this Wednesday.

More importantly, even when every museum in the state begins welcoming visitors again, it won’t be the end of this story.

'GLOBAL WEIRDING'

It has been understandably popular for media outlets to describe last week’s Texas squall as a “once-in-a-generation” or “once-in-a-lifetime” winter storm. Even climate-change believers may be tempted to write it off as a freak anomaly. After all, why would there be a link between a rapidly warming planet and the Lone Star State suddenly looking like the Snowpiercer train should be running through it?

Recent science suggests a troubling answer—one that also makes those “generational storm” labels dangerously misleading to decision-makers within and beyond the arts.

According to John Schwartz, a reporter on the New York Times climate beat, developing research hints that...

The cold air at the top of the world, the polar vortex, is usually held in place by the circulating jet stream. The Northern Hemisphere’s warming appears to be weakening the jet stream, and when sudden blasts of heat in the stratosphere punch into the vortex, that Arctic air can spill down into the middle latitudes.

In other words, evidence is emerging that Earth’s emissions-induced heating may be breaking down an atmospheric buffer that has kept the Arctic climate pinned to the Arctic landscape. This could make frigid weather more and more prone to escape its natural habitat and hurtle south, like a river bursting out of a decaying dam.

If true (Schwartz emphasized that “scientists are still hashing out all of this”), then Texas and its art world should gear up to endure more cold days in hell much sooner than a generation from now, let alone a lifetime.

They are not alone, either. Last week’s winter storm also wreaked havoc on neighboring Louisiana and Oklahoma, where Biden declared states of emergency as well.

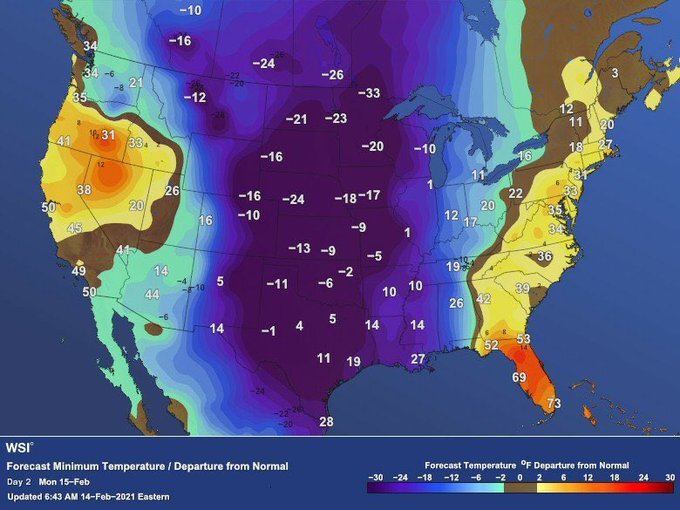

In fact, the US temperature map from last Monday showed that the same glacial weather system was punishing much of the country with brutal—and brutally unusual—cold. (The white numbers below show the forecasted temperature. The colors indicate how far the surrounding area would deviate from historical norms if the forecast bore out, with deep purple signaling a swing of minus-30 degrees Fahrenheit.)

Temporary closures aside, Texas’s cultural institutions were able to withstand last week’s winter storm via emergency measures primarily adopted to counteract hurricanes. For example, MFA Houston director Gary Tinterow told Boucher that the museum was “prepared to shelter essential staff” with canned food, air mattresses, and even dog food after lessons learned from weathering Hurricane Harvey, which flooded the foundation of the museum’s recently completed expansion and damaged construction equipment in 2017.

Like the MFA Houston, cultural institutions in Louisiana and Oklahoma likely had robust disaster-resistance plans in place thanks to their perennial vulnerability to tropical storms. But this notion only emphasizes that climate change is aiming more threats at art workers, artists, and artworks than polar episodes in warm-weather territories. Hurricanes and floods are getting more severe from the Gulf Coast to historic Venice. Wildfires are growing more intense from Southern California to the Australian Outback.

In short, climate change has become much more than just a single-disaster issue. Regionality will also matter less and less once these conditions begin driving new migration patterns likely to accelerate existing inequities of class, race, and gender—all issues that the art world ostensibly seeks to address.

As an alternative to the oversimplified phrase “global warming,” climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe deploys the term “global weirding.” It’s a more apt catch-all for the numerous abnormalities either definitively or potentially linked to the planet’s escalating average temperature. You could say that the phrase’s breadth also nods to the fact that, despite their shared origin, each of these ecological dangers imposes different demands on individuals and institutions intent on safely stewarding art and art lovers through a changing ecosystem.

But the most urgent question for museums is whether they can find patrons willing to pay for the unsexy bulwarks against these ecological problems.

BURNING CASH

Recent philanthropic history has proven again and again that major donors are far more willing to bankroll headline-grabbing architectural expansions, blockbuster exhibitions, and artwork acquisitions than boring-but-important operational needs.

This disparity has already done major damage to museums. For instance, as merciless as the Great Deaccessioning Debate has become, one of the only points where the two sides agree is that far fewer US art institutions would be combing their collections for works to sell off if plutocratic patrons were just as eager to foot the monthly electric bill as a gleaming new wing named in their honor. The myriad effects of climate change will only exacerbate this problem by imposing greater and greater behind-the-scenes costs on the already onerous financial responsibility of preserving and presenting artworks to the public.

Sure, the MFA Houston had enough generator capacity to weather last week’s cold snap, and Los Angeles’s wildfires have so far been unable to penetrate the Getty’s intricate system of incendiary defenses. But how soon will pricey upgrades be needed as global weirding intensifies? How much more expensive will it become to keep an encyclopedic collection properly climatized as outside temperatures yo-yo to higher highs and lower lows? How far will insurance premiums ascend as carriers recalculate the increased likelihood of extreme weather?

Putting up the cash to moot questions like these isn’t going to win donors the burning envy of their fellow elites at the next museum gala or Davos mixer, let alone the smoky eyes of prospective paramours during their next old-guy-in-the-club night out. These are contributions that only museum administrators and certified public accountants would love.

But that doesn’t make them any less necessary. In fact, their utter lack of sex appeal only underscores how desperately institutions will need philanthropic money earmarked for these ends as climate change worsens. Let’s hope it doesn’t take a museum full of ice-destroyed, waterlogged, or incinerated artworks to convince donors to swallow their pride and redirect their giving toward the unglamorous demands of a weirding planet.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: no matter how high the temperature rises, it’s still a cold world out there.