"Average Is Over" X: Rise of the Red Chip Artist

Previously: Parts I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX

Having used Parts VIII and IX of this series to trace the gallery system’s life lines to a future of vertically integrated e-commerce and blockbuster-dependent programming, I want to continue the palm reading session by turning to the role of the emerging artist in this new structure. Because my prior two premonitions lead to a third that heavily impacts art makers’ career arcs at the industry’s upper echelons.

As explained over the course of the past several chapters, much of the consolidation I foresee in the art market owes to buyers’ responses to the new rules of online sales. With more work by more unbranded artists becoming more easily accessible than ever via the egalitarian exodus of e-commerce, total fine art sales volume will swell, and legions of new clients will become collectors.

But with makers’ emporiums overpowering the gatekeepers and dropping the drawbridge that used to separate art creators and art buyers, the ensuing frenzy of competition will inevitably drive down the average price for an unbranded piece. So even though the number of artists generating revenue from their practice will trend upward, it may look more like supplemental income or a meager living than a lavish cash-out.

Meanwhile, high-end gallerists and high to ultra-high net worth clients alike will retreat together to the castle keep to conduct business in fortified seclusion from what they see as the unwashed, uncouth masses. Their joint interest in exclusivity will elevate blue chip prices further, and the drastic reduction in physical exhibition space enabled by full stack, branded online sales will motivate gallerists to restrict their few tangible shows to a small roster of blockbuster artists.

Together, the resulting market dynamic is what Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolffson refer to in their book The Second Machine Age as “bounty versus spread”: an unprecedented abundance of content available to all, but a gap of unprecedented dimensions between the high and low ends of the spectrum. In a sense, it’s Tyler Cowen's Average Is Over thesis stated in slightly different terms.

However, I believe in this macro picture of the art sales sector for another reason beyond collector demand. That reason is artist supply.

As we covered in Part VI, mid-level galleries are already being squeezed like an artisanal juice by these market forces. Anthony Haden-Guest, whom I mentioned briefly there, described the gallery landscape in April 2014 in almost identical terms to the blockbuster-reliant for-profit culture industries I discussed last time: studio movies, music, and books. (For a particularly striking match, flip back and compare the below to the merely two-months-older summary of the publishing industry I quoted from George Packer).

Haden-Guest wrote at the time:

One truism is that the market now governs the art business as never before and that the market is subject to the 99/1 effect, as most markets seem to be these days. What I mean by this is that there is generally one percent of winners in a market and then there is everybody else…

[I]t goes without saying that the difference that Big Money is making in the art market is one of degree, not kind. Ambitious dealers have always poached artists, knowing that if they don’t somebody else will. That said, pump up the degree enough and it becomes a change of kind too.

Now, Haden-Guest’s second point is not a new development in the art market. Elite galleries have been poaching their downstairs neighbors’ best, brightest, and buzziest talent for as long as the gallery system has existed–just as, to be fair, mid-tier galleries have been doing to low-tier galleries over the same span.

Yet if the top-down pilfering in this particular den of thieves has reached unprecedented levels, as he implies, the rampant kleptomania owes in large part to blue chip gallerists’ need to fuel the “More” Machine–a business model which, as I argued in the previous chapter, becomes not only inefficient but straight-up nonsensical in an e-commerce-heavy future.

This sea change in the sales structure twists the incentives for blue chip galleries vis-à-vis rising artists. Yes, middle tier galleries look like a fleet of sinking ships to me. In theory that makes it easier than ever for top-tier gallerists to sail by in their Jeff Koons yachts and pluck as many promising survivors off the life rafts as they want.

But without the “More” Machine squealing and shuddering for sustenance below deck–in other words, with less gallery space to fill and fewer exhibitions to program–the question becomes: How many non-blockbuster artists does it really make sense for the blue chip galleries to bring onboard in such a consolidated market? And under what terms?

It seems to me there’s a delicate balance to strike here. On the one hand, yes, gallerists will have to conjure far fewer tangible shows. On the other, I doubt that their total sales volume will significantly decline. In fact, even if, as I proposed in the last chapter, the market forces in play allow gallerists to escalate prices for their most prized artists–those who are still being honored with the rare physical exhibition–I expect blue chip art sales to increase in volume in the future.

Why? All the data that I’ve seen clearly indicates that, even though the chasm between the rich and everyone else keeps yawning wider and wider, more people than ever are managing to soar across the Sarlacc Pit to wealth. Studies published this year show that the number of households with a net worth of $1M or more–both in the U.S. and worldwide–set new records, surpassing even the pre-recession highs.

(Note: As economists like Cowen, McAfee and Brynjolffson, and most famously Thomas Piketty have clarified in their most recent books, society’s challenge from a macroeconomic standpoint is that the raw number of millionaires actually represents a declining proportion of the overall world population, which is growing at an even faster rate. In short, wealth is still consolidating at the top as upward mobility deteriorates.)

This trend suggests that elite gallerists will still have an incentive to supply more assets than their most celebrated artists can pump out on their own. True, top-tier galleries will still meet some of this excess demand by reselling owned inventory rather than strictly supplying primary market work, just as is done today. But secondary market inventory isn’t likely to be enough on its own.

Nor would either gallerists or collectors want it to be. Certain clients will always be interested in making more speculative, potentially higher-upside bets on emerging artists rather than simply clinging to the big names like an agoraphobic child to his mom’s leg in a crowded mall. For some, it’s a way to diversify their fine art portfolios. For others, it’s the guts of a venture capital-style collecting strategy in which a handful of major hits offsets a toxic sludge heap of misses.

For those reasons, unknown quantities will still have value to blue chip gallerists. That value just isn’t likely to include physical exhibitions. Not at first, anyway. Instead, rising artists will primarily be needed to fill out the supply of inventory on elite sellers’ e-commerce platforms and offer exponential growth opportunity to value-conscious collectors.

The outcome that makes sense to me, then, is the creation of a designated second tier of artists within blue chip galleries’ rosters–under terms even more favorable to sellers than the current standard. Think of them as the red chip artists, i.e. the second most valuable currency at the art market’s high stakes gaming table.

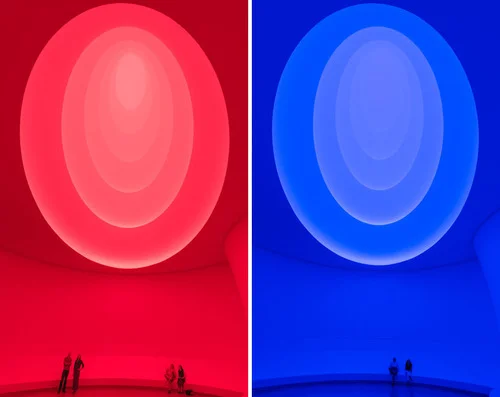

While top tier galleries’ most celebrated, most established artists continue to receive the privilege of physical exhibitions and the apex of the price pyramid, the red chippers would only be sold in the galleries’ independently operated digital storefronts initially. However, the gallerist would also entice red chippers with the opportunity to elevate to the exhibition-worthy blue chip tier–the James Turrell/Jeff Koons level–provided they’re sufficiently profitable online.

The parallel would be to the way that a major retailer tends to roll out a new product: an exploratory trial in a small number of franchises, followed by expansion if sales are brisk. Put simply, it’s about proof of concept. Couching the process in those terms will undoubtedly make some people squirm like a colon full of tainted Indian food, but it makes perfect sense from a business standpoint.

Both today and in the past, that proof of concept would normally arrive in the form of profitable and well-received exhibitions at mid-tier galleries. But in a future where mid-tier galleries are an extinct species, blue chip gallerists will have to don their safari gear and patrol new proving grounds.

The logical territory for this hunt to take place in a future of robust fine art e-commerce would be the makers’ emporiums and artists’ own independently operated sites. Elite gallerists could identify and seduce the most successful and most sought-after independents, then plug them into the gallery’s own vertically integrated digital sales platform as a low-risk, potentially high-reward trial.

Blue chip gallerists would thus maintain the ability to harvest promising younger talent while keeping their inventory sufficiently stocked and their overhead appropriately low. The bulk of the sellers’ resources, monetary and otherwise, would remain dedicated to the blockbuster artists on their rosters. And those bigger, safer bets would be virtually guaranteed to keep the profit nucleus intact.

Broadly speaking, the process I’m describing is a natural evolution of the current system. The standard playbook is for a blue chip gallery to introduce their emerging talent in one of two ways–both of which only deviate from my predicted e-commerce-based, red-chip-to-blue progression in the sense that they all take place in physical spaces.

The first is a smaller solo exhibition that supports a larger one by a more established artist running concurrently in the same building–the equivalent of a Hollywood studio fronting their expected blockbuster with the trailer for a lesser known but highly promising flick also on their slate. The second is to include a recently signed artist’s work in a group show that mixes big names and emerging ones in the same context, providing the newly signed talent some shine by association–the equivalent of a hip hop megastar giving other artists in his crew feature verses on his next single.

In both cases, gallerists also begin privately trotting out other available works by the new talent to interested clients in their back rooms as soon as the ink is dry on the representation agreement (you know, if anyone in the art world regularly signed contracts). Together, the strategy sets the stage for the freshly anointed artist prior to the moment the spotlight swings her way for her first grand solo under the gallery’s roof.

For example, David Zwirner took on Oscar Murillo in September 2013 and presented his avant-garde Willy Wonka solo exhibition, A Mercantile Novel, seven months later. I can’t confirm it, but I’d pledge to passively watch you vandalize my car if Zwirner wasn’t already trotting out Murillo’s paintings and other more traditionally commoditizable assets in his back room during the intervening months.

But while the proof of concept playbook remains basically unchanged on a strategic level, the caveat for potential red chip artists is the term sheet they’re likely to receive in an e-commerce heavy future. With gallerists’ no longer needing them to supply physical exhibitions, and with their opening price points offering lower margins relative to their blue chip stalwarts, I would expect gallerists to add a heavy dash of bitters to the business arrangement. Most likely, that would take the form of an even meatier sales commission than the traditional standard–say, 60 or 65 percent rather than the typical 50 percent.

Faced with the chance to transition from the makers’ emporiums or their own hustle to the branded, consolidated galleries, artists with red chip offers would thus have to weigh the question of long-term growth potential.

Would it be better to net only 35 or 40 percent of a higher, branded gallery sales price, or 70 percent of a lower, makers’ emporium sales price? What about 100 percent of a deal closed on one’s own platform? Even with minimal resources devoted to her cause, a red chip artist could be primed for greater profitability and scalability strictly through the glow of a top tier gallery’s branding than through her more independent alternatives.

And even if that’s not the case at the jump, what if the more extreme red chip peonage is indeed only temporary? Assuming an artist does real numbers on a blue chip gallery’s digital marketplace, her seller then has the incentive to elevate her to the exhibition-worthy blue chip tier. That means more favorable margins–probably back to the typical 50 percent–on higher prices, and theoretically, somewhat more support and security than roaming the mountains as a lone wolf.

The system I’m describing would create powerful motivations for artists to build their own brands in an effort to make themselves attractive to the handful of elite galleries capable of supercharging their careers. And such an environment, in turn, suggests to me that there will be an opening for a new (or at least, newly empowered) third party to carve out a niche for itself in this disrupted ecosystem. I’ll detail its identity and possible role in the next chapter.

Jump to: Part XI