Average Is Over XI: A.I.M. for the Soft Spot

Previously: Parts I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X

The e-commerce-based shifts I’ve predicted over the course of this series represent disruptions of the art market at both operational and strategic levels. The macro result of those disruptions is a future gallery system true to my original inspiration, Tyler Cowen's Average Is Over: one in which the combination of technology and smart business will accelerate the fine art sales industry’s evacuation of the middle in favor of a Great Migration to the economic extremes.

However, as in any other industry, eliminating old inefficiencies often leads to the growth of new ones elsewhere in the sector. And every inefficiency serves up the potential for innovation. What I’d like to focus on today is how the future gallery system’s grand restructuring around online sales will create an opportunity for an entirely novel player to emerge in the field.

By now we’re familiar with the main camps I foresee in this brave new art world. On one side: the makers’ emporiums, all-inclusive marketplaces ready to do wired business at the low end of the price spectrum–in both comparative and, increasingly, absolute terms–with any honest buyer, regardless of her lack of pedigree or net worth.

The works available in these venues will be supplied by a vast motley crew of unbranded artists operating without allegiances to any traditional gallery or representative. The makers’ emporiums offer these artists not just an open, high-exposure e-commerce platform and the possible attention of every pair of pupils that browses it, but also nearly unlimited freedom to chart their own commercial course, from the types and quantities of pieces they produce to the price points they set–and all of these benefits come in exchange for a significantly lower percentage of their profits than what a traditional gallerist would demand.

Alternatively, unbranded artists will also retain the option to sell directly through their own websites or social media feeds, as some are already doing today through Instagram. (A phenomenon which both others and I have covered before). While the independent route lacks the pre-awareness advantage of prominent makers’ emporiums like Saatchi Art, it allows art-makers to net the full price of every sale–an upside that deserves better than to be chucked into the nearest dumpster without serious consideration.

But freedom ain’t free, as plenty of screeching bald eagles on red state bumper stickers will remind you. The liberties enjoyed by artists selling through either the makers’ emporiums or a self-run platform come at the cost of being plunged into a violent throng of competitors, with few clear ways to differentiate themselves and little if any professional guidance about the strategies available.

Unless each individual artist can figure out how to crack the code herself, the sheer volume and intensity of the rivalry will pressure her to react in the most obvious way: by dropping her prices. The luster of being able to sell work so democratically then gets devoured by the sobering economic reality of lower returns. And at that point, open e-commerce’s utopian facade crumbles, revealing the termite-eaten framing and cracked foundation of a career as an unbranded artist–which may not be a sustainable career at all.

At the complete opposite end of the market we’ll find a handful of exclusive blue chip galleries, all vertically integrated more thoroughly than ever through the adoption of full stack e-commerce. Their clientele will consist of the same gourmet serving-size of global plutocrats feeding today’s art market, with the works that change hands in this nearly impenetrable bistro all priced at the uppermost limits of good taste.

As the rise of online sales minimizes the need for both physical gallery spaces and the artists needed to fill them, elite branded sellers will also trim their rosters wafer-thin. The few physical exhibitions on their programming calendars will be handed to a small cadre of established superstar-level talent whose artistic narratives and production have been carefully shaped over time in collaboration with the gallerists themselves.

Meanwhile, the inventory in each high-end gallery’s digital marketplace will be filled out by a painstakingly curated group of promising young talent plucked from the unbranded swarm. These artists will be marketed by top-tier sellers at still lofty but somewhat lower “red chip” prices meant to appeal to collectors interested in growth potential–an attribute the gallerist can help manifest by giving the red chippers the type of informed guidance they lack in the makers’ emporiums.

For their part, the red chip artists will likely achieve higher prices through their newfound brand affiliation than they would in any unbranded marketplace. But in exchange they will be forced to surrender a significant amount of their independence and a larger percentage of their profits to the gallerist, who has the leverage to adopt a strict “my way or the information superhighway” stance.

This pocket summary illustrates that, despite ostensibly serving the same basic function, the low and high end of an e-commerce-heavy art market will be perfect opposites of one another in most respects. Each will be able to think of the other as its evil (or at least hopelessly misguided) twin.

But viewed from just the right angle, both sides of the market do share one trait: In their own ways, they both thrust sub-superstar level artists into a position of weakness.

The makers’ emporiums–and even more so, the self-generated, self-operated platforms–effectively leave artists to figure out their own business plans. And while art history contains prominent exceptions, I don’t think it’s out of bounds for me to suggest that disinterest or deficiency in career game theory is a major contributor to many artists’ decisions to pursue the fine arts as profession in the first place.

Meanwhile, the red chip arrangement theoretically provides the artist with the valuable mentorship of the blue chip gallerist. But it also severs the artist’s spinal cord on every strategic choice, from what type of work she should create to how fast she should produce it to what other projects and opportunities she should pursue outside of stocking her gallery’s online inventory racks.

The red chip artist thus becomes a negotiations quadriplegic. If she objects to her gallerist’s vision, who else will assist her? If she decides she’s fed up with being big-timed, how mobile can she really be in a gallery system with so few elite sellers and so few vacant slots for young talent–especially if her activities and connections to the rest of the industry have long been restricted by the first gallerist’s whims a la Kathy Bates in Misery?

What each of these scenarios reveals is the same underlying market inefficiency–the one that I alluded to in this post’s introduction. They show that at all levels of an Average Is Over art market, artists will have an acute need for industry-savvy, commerce-minded allies unaffiliated with any gallery or selling platform–strategic partners loyal to the artist’s interests and only the artist’s interests.

These individuals would therefore “represent” artists in some of the same ways as a good gallerist, while at the same time retaining the autonomy to act as a kind of free radical in the marketplace. They would provide vital career guidance in the absence of a gallerist–and a formidable counterpunch in the presence of a narrow-minded or hard-bargaining one. They would help bridge whatever terrifying, car-devouring sink hole yawned open next on the artist’s road forward.

I’m going to dub these new players AIMs, short for “Artists’ Independent Managers.” I believe their evolution is inevitable. And I believe it in part because, aside from the vision of the industry that I’m drawing from my tarot card deck in this series, the current art market already provides precursors for their rise.

We can find the developmental roots of the AIMs in a pair of existing free radicals: the art adviser and the independent curator. Both parties are themselves relatively new to the field, having only ascended to real prominence during the EKG graph of spikes and troughs that is the commodity-minded 21st century art market. But in a sense, both have carved out their respective niches in response to some of the same conditions I’ve addressed in this series.

Of the two, art advisers bear less resemblance to the model I’m proposing. The main parallel is their status as independent actors darting freely through the industry, surveying any and all possible business opportunities for their clients without the burden of a physical gallery space weighing them down.

But crucially, their clients are collectors, never artists. Collectors essentially hire art advisers to act as their cultural bloodhounds. Their job is to hunt anywhere and everywhere in the market to identify and acquire quality works to their clients’ tastes at appropriate prices. That search leads them through every sector of the industry: galleries, secondary market dealers, art fairs, auction houses, even directly into artists’ studios.

Art advisers just never cross the commercial divide by representing suppliers of any stripe. This choice partitions them strictly to the demand side of the market, making them a kind of photographic negative of what I envision the AIM to be.

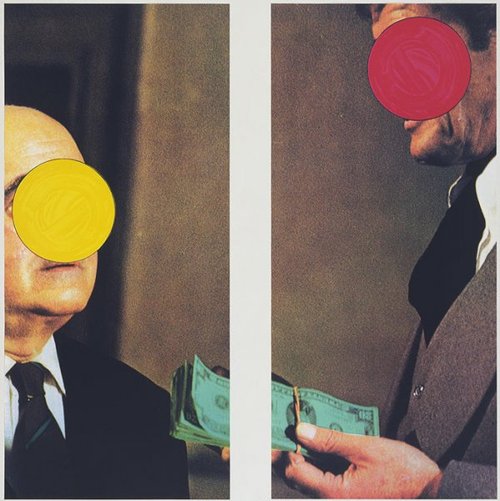

The closest that advisers generally inch toward acting on behalf of suppliers is through the common yet dubious practice of striking back room pacts with gallerists or dealers to recommend their inventory in exchange for a second sales commission–a (to me, flagrantly unethical) move that means the adviser gets paid by both parties she stands between in any fine art sale.

And while I’m sure some advisers have done the same to artists when buying directly from them, this mustache-twirling deviance is a far cry from representing artists in good faith, as AIMs would thrive by doing.

Much closer to the right model is the independent curator. Her role in the present day ecosystem is to promote artists whom she believes in without officially binding herself to a single gallery, venue, or collector over the long haul. This feat is normally accomplished through organizing on-demand exhibitions in spaces either: A) permanently held by sellers or arts nonprofits, or B) temporarily secured through her own efforts.

The core difference between the independent curator and the AIM is that in general, the former still does not actually represent artists in any formal sense–by which I mean maintaining long-term quid pro quo relationships with them. Instead, each project for which an independent curator champions an art-maker qualifies as what the entertainment industry calls a ”hip pocket“ deal–a self-contained, one-off arrangement with no further expectations about the future on either side.

This is not to say that independent curators never work with the same artist repeatedly. Often, they do. They just have no continuing obligation to do so–and certainly not one that would ever (cue pipe organ scale and blood-curdling shriek) be memorialized on paper.

Unlike art advisers’ (ostensibly) monogamous commitment to collectors only, independent curators tend to maintain broader client bases. They can be retained by galleries, nonprofits (including museums and foundations), and other paying parties as well as individual collectors.

Independent curators’ responsibilities don’t fundamentally change in any of these cases. They still exist to program shows or coordinate commissioned works by linking their clients to favored artists. They just aren’t (in my experience) ever being contracted–and thus, primarily compensated–by the artists themselves.

And compensation matters. A contrarian could argue that, even if approached by a gallery or private foundation, an independent curator is still performing the same job as an AIM, i.e. promoting artists she feels are under-represented. But I would reject that argument like a restaurant salad with a dead baby rabbit nestled in the greens.

Why? Because always and forever, compensation orders our incentives.

To the surprise of absolutely no regular reader of this blog, set payment guidelines do not exist for independent curators. But my understanding is that they generally either A) take an up-front fee from the client for whom they’re programming an exhibition or project, B) if said project is for profit, agree to receive a percentage of sales generated–usually out of the client’s cut, or C) both, with the size of the up-front fee reduced to account for the potential back-end gain.

Regardless of the exact form of payment, an independent curator being compensated by any party other than an artist can, should, and most likely will behave with that party’s interests foremost in her mind. And that means that the artists the curator contacts to fulfill her duties can never be fully sure she has their best interests at heart.

Does this mean artists should refuse to work with independent curators in the present day? Not at all. Opportunities are still opportunities, even if they’re imperfect. But this basic business reality does mean that a loyalty gap exists between the independent curator and the AIM.

For this reason–perhaps counterintuitively–the AIM’s closest existing comp is not in the visual arts at all, but rather in another of the for-profit culture industries we’ve discussed. That comp is the Hollywood talent manager, who exclusively works to develop and promote a stable of writers, directors, and/or actors in exchange for commissions on the paid work she generates on their behalf.

How exactly does a manager do this? Though each of the above genres of movie industry talent has its particularities, all managers’ work revolves around twin suns: helping their clients to maximize the quality and appeal of their new material, and marketing their clients to anyone and everyone who could potentially hire them–whether "hiring” means buying a script, signing them to direct a movie, casting them in a role, or any of the other permutations of entertainment industry deal-making that keep your screens overflowing with glorious (and not so glorious) content.

But the most meaningful separation between the Hollywood manager and the independent curator is that the manager’s incentives are perpetually aligned with her clients’. Because with one minor caveat, she only gets paid when they do.

The standard manager’s compensation is a 10 percent commission on the dollar value of any deal struck in part through her influence. So if a screenwriter she represents sells a script for $100,000, then $10,000 becomes a burnt offering to the manager for her assistance, and the writer’s net shrinks to $90,000 (before taxes, union dues, and separate commissions to a contract attorney and an agent, if applicable).

But in theory, that’s still $90,000 more than the writer would have earned without the manager–not to mention a staggering 40 percent more than an artist would pull in if chained to a standard gallery representation deal.

Now, about that minor caveat I mentioned: I believe that large management companies like Management 360, Circle of Confusion, and 3 Arts pay their individual managers a salary in lieu of the actual commissions for the deals they book, which go to the firm’s partners. But even in these cases, the additional safety net doesn’t skew the managers’ incentives in the same way as an independent curator’s being hired by a collector.

This is because any manager failing to generate commissions isn’t going to be receiving a salary for long either. So while working at a large company may not make a particular manager quite as hungry as the truly free radicals–her independently operating peers who only eat when their clients do–her loyalties to the people she represents remain secure.

An AIM compensated and operating like an entertainment industry manager would therefore offer huge potential benefits to an unbranded artist in the commercial melee of this future art market. With artists more responsible than ever for their own destinies, those destinies will be determined by the strength of the followings they’re able to amass without the help of a gallery. The skeleton key to success will be in self-generating hype.

The basic laws of economics are the same whether an artist is offering her work on a makers’ emporium, an independent platform, or a blue chip gallery: For any asset only available in limited quantities, price rises with demand. And in the art industry, demand is largely determined by prestige.

As we covered during Part VI, in the past (and persisting into the present day) the stairway to prestige had clear and gradual steps. Low-level galleries and mid-level galleries formed a natural progression to high-level galleries, and complementary career boosters like museum shows, critical accolades, and acquisitions by prominent collectors (public and private alike) rose alongside them like banisters.

But in a version of the industry reshaped by e-commerce, the stairway to prestige twists and warps into a mind-bending M.C. Escher-like architecture. The disintegration of mid-tier and low-tier galleries also means the disintegration of the personal guidance and promotional benefits that artists used to receive at the earlier stages of their careers from the people operating and buying from those galleries. Every artist trying to figure out the path forward becomes Jennifer Connelly in the climax of Labyrinth.

Hence, the need for AIMs: knowledgeable, well-connected professionals working on behalf of unbranded artists to guide them through the maze by any means necessary. Free of all restrictions and working on commission, they have every incentive to be relentless, resourceful, and utterly monomaniacal in their pursuits of opportunities for the artists they represent.

It won’t be an easy job. The AIMs’ responsibilities will vary widely depending on each represented artist’s specific needs, progress, and ultimate goals. They must be able to do everything from organizing pop-up exhibitions (in the vein of today’s independent curators) to reviewing contracts and consulting on potential offers to feverishly promoting their artists to any third party with the potential to elevate said artists’ prestige levels. That cohort of third parties includes but ain’t limited to:

*Blue chip gallerists (and their trusted staff), in an effort to push the AIMs’ artists as possible red chip candidates;

*Private and institutional collectors, especially young ones interested in “growth artists” but lacking the resources to pay red chip prices;

*Auction house specialists, who are likely to become more and more open to offering works by artists sans gallery representation as gallery rosters contract;

*Marketers and Creative Directors at edge-conscious corporations and advertising agencies, i.e. those slavering to chase the cool through the types of branded content commissions we’re seeing more of everyday–such as Doug Aitken’s Levi’s-sponsored Station to Station extravaganza in 2013.

Just as importantly, AIMs would also use their knowledge of the market to guide their clients toward creating both the most sought-after types of artwork and the most captivating personas/narratives to frame them.

Hollywood talent managers serve both these functions now. Their mission is to hone each client’s creative output and image within the industry for maximum commercial viability based on market trends–both short-term and long-term.

And even though that comparison may make an art purist’s skin feel like it’s being invaded by an army of skittering centipedes, the truth is that accepting such (hopefully) wise counsel is likely to give unbranded artists an edge over their AIM-less competitors in the Hunger Games arena of the unbranded, online sales-heavy art market.

Some of the AIMs’ knowledge would be gained through the types of old school peer-to-peer networking mentioned above. But in the best cases, the pavement-pounding and glad-handing would be augmented via machine-enabled industry analytics, similar to what the savviest blue chip gallerists will use to blood-dope their own businesses, as we discussed in Part VIII.

In fact, top quality AIMs could also be a major weapon for artists who transition into red chip–or even blue chip–status, as I briefly mentioned earlier in this chapter. Ascending to the ranks of the elite simply alters the set of challenges an artist faces. Once again, the AIMs’ role would simply have to morph to meet their branded clients’ different needs. But for the sake of all our attention spans, I’ll wait until the next installment to describe what strange new beasts the AIMs can help artists slay at these higher elevations.