Making Yourself Scarce

While I was cruising Twitter yesterday, I caught a tweet from Sotheby’s advertising (and really, isn’t that the right word?) that a Mike Kelley work on paper called The Past and the Future had just hammered down at $305,000 in their latest Contemporary Curated sale in New York. The price qualified as a more than 6x multiple of the piece’s low estimate and more than 4x of the high ($50,000 - 70,000). And after looking at the subject matter in the larger context of Kelley’s work, I got to thinking about a unique kind of overpay that can happen in the market for an artist of his stripe.

Say you replicated the face-palming “gotcha” scene in every lazy conspiracy thriller of Hollywood’s past quarter century by secretly tape-recording contemporary art enthusiasts’ candid opinions on Kelley. You’d come away from your bizarre sting operation flush with audio confirming two points of consensus: One, that he was hugely influential to a generation of artists working in multiple media, especially here in LA; and two, that the vast majority of his output is, frankly, hard to enjoy.

The reality is that Kelley, who committed suicide in 2012 at age 57, was a perpetually tortured soul, at least in private. I’ve heard accounts from former students, studio assistants, and others who all portray that agony as a strictly inward-facing phenomenon–that to friends and collaborators, Kelley was a jovial, kind, engaging presence for most if not all of his adult life.

Still, it’s flagrantly obvious from his work that the man contained a legion of demons intent on skewering him from inside out. I left his retrospective at MOCA this summer completely drained by both the onslaught of artwork and the distress it embodied. The exhibition contained over 250 pieces ranging from video to drawings to sculpture to mixed media, and few of them emitted even a single faint beam of sunlight.

In fact, I think it’s fair to say that the lion’s share of the show–and Kelley’s lifetime output–oscillated between disturbing and openly transgressive. Piece after piece suggested that Kelley built his career on consciously trotting out his anguish and self-loathing for full frontal public exposure. I constantly felt as though he was explicitly challenging viewers to look away while secretly praying they wouldn’t be so callous. Emotionally and visually, I found it to be an exhausting experience. And I know I wasn’t alone.

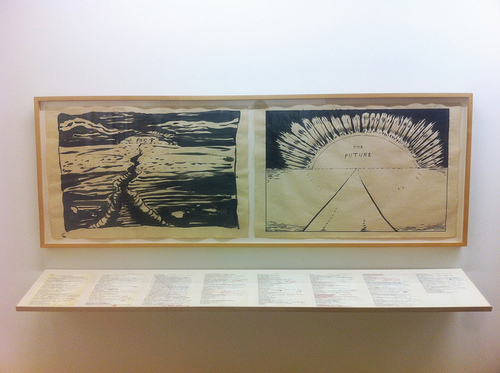

But you wouldn’t know any of that by looking at The Past and the Future, a simple, even optimistic acrylic-on-paper diptych of the sun setting and rising over separate gestural landscapes.Compare it to something like Odalisque (2010), Eviscerated Corpse (1989), or the NSFW Sinister Forces (1976/2011), and the tonal contrast hits you in the retina like an expert sniper’s bullet.

As those other three examples indicate, The Past and the Future is one of the rare Kelley works that a collector could install anywhere–her home, her office, her charitable foundation–and truly live with, without making herself or others vulnerable to the mud slide of dread that that he spent decades flooding the hillside with.

I can’t prove it, but my hunch is that this is a big part of the reason a work like The Past and the Future blows past its estimate like Maverick buzzing the tower in Top Gun: A collector gets all of the art historical cache–and thus market juice–of a revered artist, but without incurring any of the psychic costs of the difficult work most responsible for his legacy.

If so, it’s a complete inversion of the market’s normal valuation rules. Every artist has particular works or series that are deemed more valuable than the others. But those “legacy pieces,” let’s call them, are generally the ones that best capture his voice, that most clearly embody his signature style and most clearly communicate his iconic themes.

The Past and the Future is not one of those legacy pieces. In fact, it’s not even characteristic of Kelley’s other black and white works on paper, most of which (from what I’ve seen) slide headfirst into the same tortured and profane muck of his mainstays. It’s an anomaly, a minor attraction, a misdirect.

And that’s the point. In the case of an artist like Kelley, there’s a very real chance that the most price-inflated assets in the commercial market will be the rare few that cut against the confrontational, disturbed grain that defined him: kinder, gentler pieces like The Past and the Future.

The resulting irony is that, for an artist who produced work at such a prolific rate, Kelley actually imposed a strange type of scarcity on himself. The total number of pieces he created was enormous. Yet the number of viewer-friendly ones within that mass is comparatively tiny–a few odd flowers managing to grow amid the carnage of a collapsed meat-packing plant.

This is not to say that his more unsettling output doesn’t still fetch high prices. Kelley is firmly entrenched as a branded, blue chip artist by now, repped by the likes of Gagosian, Skarstedt, and Acquavella, with major solo museum exhibitions on his CV and works in prominent public and private collections across the map. His table in the VIP room is secure forever.

Plus, it would be naive to assume that every collector who buys work these days is actually going to hang it somewhere visible anyway. Even an unavoidably explicit Kelley piece like Three Point Program/Four Eyes (1987), a felt banner emblazoned with the text, “Pants Shitter & Proud P.S. Jerk-Off Too (And I Wear Glasses),” can’t trigger any offense if it’s tucked away in a climate-controlled storage locker until its owner sees an opportunity to resell at a tidy profit.

Nevertheless, the point is that the scarcity of approachable assets in Kelley’s body of work makes the few, the proud, the livable likely to be drastically over-valued relative to their significance in his career. It’s a market inefficiency that wrongly favors the attractive over the important. Consider it a rookie mistake.

But the insanity of the market isn’t driving the outcome by itself. In fact, from a viewership standpoint, the buyers are arguably acting at peak rationality. It’s just that, in paradoxical cases like these, the short supply of pretty assets tends to make them comparatively ugly investments.

Keep that in mind the next time an uncharacteristically tame work by a transgressive artist does backflips over its estimate. It will happen soon enough. Because in terms of certain collectors’ behavior, The Past and the Future is exactly that.