Speed Kills: Museums & Discretionary Art Acquisitions

In the summer of 2003, I was one of nine interns in the Education department of The Cloisters. My primary job while there was to lead tours of the museum’s collection and gardens for packs of kids in New York-area summer camps, youth groups, and school programs. If you think Medieval art is musty and static, I assure you that the excitement level spikes when you know that at any moment during a walkthrough a couple of nine year-olds jacked up on Mountain Dew and Pixy Stix may start drop-kicking each other within inches of a 12th century wooden altarpiece. The Middle Ages come alive quickly in that context. (Also, the art is legitimately great.)

However, every Monday, when both The Cloisters and the Met’s main location were closed to the public, all of the interns in all of the museum’s departments engaged in some kind of planned, behind the scenes educational activity. The most sanctified of these events was a Q+A with the Met’s then-Director, Philippe de Montebello. The bulk of the session consisted of Montebello’s discussing a broad range of topics with another high-ranking executive or curator: museum practice in general, the Met in particular, his own journey to the Director’s throne, and a variety of other subjects that, admittedly, I’ve mostly forgotten.

But after the main event, Montebello took questions from the intern legion. One of those questions came from me, partially because I thrive on competition and there was an informal one going among the museum’s different intern-wranglers as to whose summer help would be least intimidated in the king’s court. I have no doubt my question came in less precise verbiage, but I asked Montebello something along the lines of this: Since a central part of any museum’s mission is to acquire and exhibit works that legitimately qualify as “art history,” how does the contemporary department figure out what’s worth collecting, seeing as, unlike their colleagues in other departments, they have little if any historical distance from the work? In other words, how do you know what’s worth buying while the story of the current era is still being written?

If memory hasn’t betrayed me like an ill-timed boner during a class presentation, Montebello’s answer was that all potential new acquisitions, no matter what their historical epoch, went through the same rigorous institutional review process. Yes, practically every other department in the museum had sturdier information about which works mattered in their own fields than did the contemporary department; time, scholarship, and other collecting institutions’ actions had largely passed judgment on the rest by now. But while most of the responsibility of choosing legit artwork fell on the post-war curators, the museum’s acquisitions apparatus had been designed around thoughtful checks and balances. Nothing entered the hallowed halls of the Met’s collection without thorough oversight and careful consideration.

I was reminded of all of this when I read a story a few days ago about the Victoria & Albert Museum’s adoption of a new acquisitions policy and micro-department. Dubbed “Rapid Response Collecting,” the dual initiative rejects the plodding bureaucracy of typical museum acquisitions in favor of a discretionary spending model. The targets, according to the press release, are contemporary design and architecture items that will help the museum to “be responsive to global events, technological advances, political changes or pop cultural phenomena that have an impact on” visual culture. Examples cited in the release include an Ikea soft toy, the first 3D-printed gun, and a pair of Primark jeans purchased after the deadly collapse of the Rana Plaza garment factory in Bangladesh last year.

No formal requests, no committee meetings, no sloth-like institutional review will be needed to acquire these pieces. A chunk of cash is apparently ready and waiting in a reserve fund, allowing the new department’s curator to see the object, value the object, and buy the object without going through a lengthy administrative process.

This policy shift is not quite as radical as if the College of Cardinals elevated an out lesbian to the papacy, but it’s still significant. Most museums (at least the major ones) tend to use a tiered acquisitions policy with hurdles that rise in lockstep with the desired work’s price. The more the piece costs, the more intense and collaborative the review becomes.

For instance, the Met's guidelines create four value tiers. Once a department’s curator formally recommends a piece for acquisition - a process that begins with the writing of a detailed report and, for works not fresh from the studio, possibly an analysis by conservators and scientists - the price tag determines who needs to sign off. Departments can acquire single pieces valued at or below $25,000 as long as the department head approves. Works priced at $25,001-$75,000 require the consent of both the department head and the museum’s Director. Anything costing between $75,001-$150,000 needs the approval of the department head, the Director, and the chairman of the museum’s Acquisitions Committee. And if the work’s price tops $150,000, it must be approved by the Acquisitions Committee as a whole.

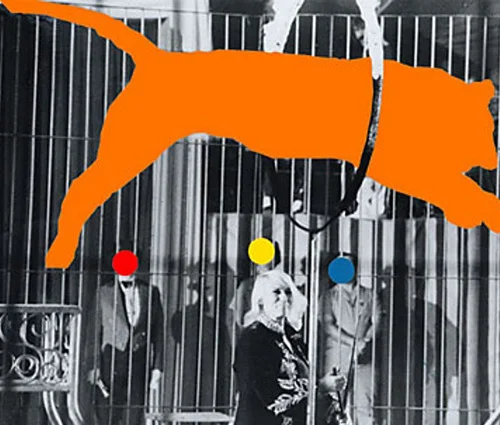

Needless to say, this structure does not exactly enable museums to move with the sudden quickness and powerful closing speed of jungle cats.

The Victoria & Albert’s Rapid Response Collecting changes the equation. It not only removes the usual bureaucracy (and the resulting slowdown) of acquiring artwork, but also sets aside a permanent museum gallery dedicated to the immediate exhibition of the newly acquired pieces. Doing so strips away at least one more layer of institutional review, as it can be just as laborious to decide which pieces of the collection should be exhibited at any given time as it is to decide to buy the pieces in the first place.

Before I go further, it’s worth emphasizing that the objects being acquired in the Rapid Response initiative all sell for an extremely low value, at least relative to museum-quality artwork. I’m sure that Corinna Gardner, the program’s curator, had to do more than sing a pleasant tune to get her hands on the world’s first 3D-printed gun, but the price was likely still pocket lint in comparison to the work of a blue chip or emerging star contemporary artist. And I have no doubt I’ll sleep comfortably tonight after declaring the same about a plush Ikea toy. In that sense, it’s a low cost, low risk experiment, and I want to be careful not to read too much into it at this early stage.

Still, what I find most interesting about Rapid Response Collecting is that it theoretically allows a museum to behave much less like a museum and much more like an art dealer or private collector - notably, the two entities with a distinct efficiency advantage over museums when it comes to acquiring artwork. If the burden of peer review disintegrates, the museum is free to act with the velocity of its non-institutional competitors. It can react to the pulse of today, buying quickly and installing (or de-installing) just as quickly, with no second-guessing or validation needed from some higher power.

This development seems most meaningful in contemporary art, which now functions as a speed and volume business, as I’ve argued once and again. With new works being bought and sold faster than ever, it becomes increasingly difficult for a museum hamstrung by checks and balances to be a player in the marketplace. For that reason, I would not be surprised to see other institutions adopt this innovative portion of the Victoria & Albert’s model, at least on a trial basis, for some part of their own contemporary departments. Nixing the traditional oversight process might put museums - especially those without A-level name recognition - in a better position to succeed against the private sector. Fight fire with fire, as the cliche-spouters would say.

Yet a bramble of thorny questions would grow out of a trend toward efficiency in museum acquisitions. Returning to my question as an intern all those years ago, the museum’s traditional role in the art world is to validate the best of the best, to thoughtfully consider the arc of art history and judge who deserves access to the pantheon. The Victoria & Albert’s Rapid Response experiment does not disrupt that role thanks to the program’s narrow jurisdiction and the comparatively low value of the objects within it. But if the model spreads to other institutions and expands to include pricier works, it would begin to blur the boundary lines between museums and the types of collectors who preference fast action over sound strategy.

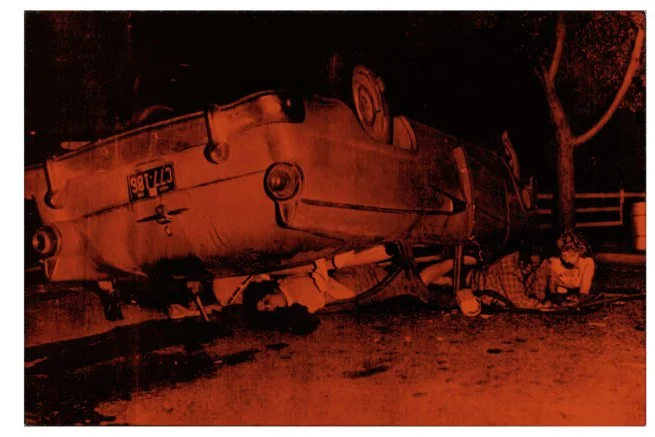

To be fair, speed isn’t inherently fatal. Not as long as you’re still making good decisions while you accelerate toward the sound barrier. But if we’ve learned nothing else from the economy in this generation, we’ve learned that dismantling a system of checks and balances can quickly plunge entire industries into turmoil. Moving faster doesn’t automatically mean moving smarter. In many cases, it can lure people into doing the opposite.

So for now I applaud Rapid Response Collecting from an efficiency and innovation standpoint. Nevertheless, I’d advise museums to be cautious about implementing and expanding their own versions. I think there’s a happy medium out there. But if the museum acquisitions model changes too quickly, too dramatically, and too thoroughly, trouble could lie ahead. The changes may benefit museums in the short term, as they would be able to better compete for glitzy names in a churning marketplace. But I wonder if it benefits either them or the public in the long term, when history will have had a chance to pass judgment on the decisions made in the frenzy.