Two Quotes, Two Careers: Jeff Koons & John Waters

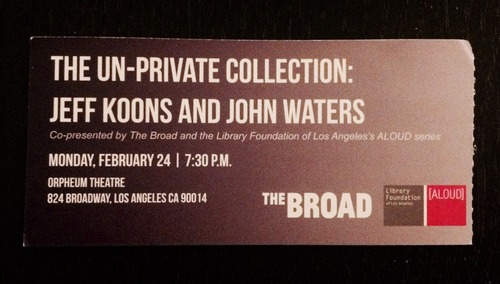

Last night I was fortunate enough to attend a conversation between shock (and schlock) cinema impresario John Waters and perpetual Gray Market conversation piece Jeff Koons. The event was the 2014 debut of The Un-Private Collection interview series jointly presented by The Broad Museum (set to open in DTLA in 2015) and The Library Foundation of Los Angeles. By pairing artists prominently represented in the museum’s collections with like-minded figures in related disciplines, the program seeks to tease out new thoughts and appreciation of the artists’ work. And while that definitely happened for me tonight, I’m not sure that it happened in quite the way that anyone involved intended.

Koons and Waters were arranged-married, according to the introduction given by The Broad’s Founding Director, Joanne Heyler, because the ideas of “good taste” and “bad taste” factor heavily into the dialogue surrounding both men’s work. Waters, after all, is the writer/director whose most (in)famous movie (Pink Flamingos) features a transvestite named Divine scarfing human feces, and Koons is the creator of an entire body of work (Made in Heaven) centered on explicit portrayals of himself pleasuring his then-wife, Italian porn-star-turned-Parliament-rep Ilona Staller, in a variety of different positions. It would be reductive to frame the two men as mirror images of one another, but suggesting a strong thematic link between some of their work doesn’t exactly require a treasure map hidden on the back of the Declaration of Independence.

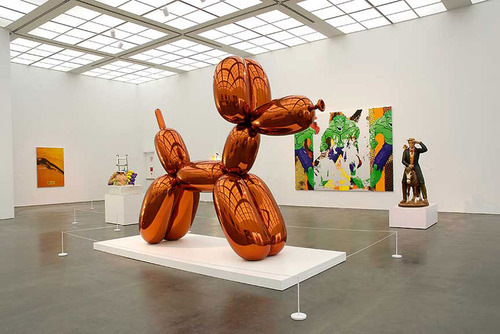

However, what struck me about the conversation is what vastly different careers Koons and Waters have led despite their related content. Koons has his detractors, but overall he has been wildly successful from both a critical and a commercial standpoint; a retrospective of his work will be The Whitney’s curtain call in its current building, and his Balloon Dog (Orange) set the record for the highest auction price realized by a living artist at Christie’s this past November.

Waters, on the other hand, has never risen past niche status as either a director, an author, or an artist. He is beloved by a certain caliber of film buff and/or guardian of the fringe, but he will never be a household name or an entry on any Forbes lists. Their respective examples tell us a great deal about the consequences of branding in the arts, precisely because Koons and Waters define polar opposites on the spectrum of success. And I believe I can sum up the difference with a single quote from each man during last night’s fireside chat.

Let’s start with Koons. Late in the conversation, he started recounting the types of jobs he worked growing up, almost all of which hinged on sales skills - a fact that Waters was quick to point out. Koons at first downplayed the idea, then turned around and embraced it by declaring without a granule of irony that “Sales is the front line of morality.” Waters asked him to repeat the sentence, and he did so dutifully. Koons went on to try to both humanize and intellectualize an idea that could trigger a stroke in most art purists.

To paraphrase, what makes selling moral to Koons is that, to be effective, a salesman must abandon all judgments at her customer’s doorstep. The potential client’s appearance, the odor emanating from their house, or the world views they espouse have to be accepted by the salesman without judgment, or else no connection - and no sale - will take place. In that sense, selling makes all involved more virtuous, because it demands that we set aside the shortcomings of our fellow man and find common ground.

The quote was a perfect crescendo to Koons’s commentary the entire night. Every answer he gave to his counterpart’s inquiries was thoughtful, articulate, and in my view, carefully sanitized. He met every image of his own work that Waters had chosen to guide the conversation with a high-minded and (ostensibly) sincere narrative of artistic ideals. Whether he was invoking Plato vis-a-vis an inflatable Easter bunny sculpture or extolling Lady Gaga’s virtues as a vanguard of creative freedom, Koons effortlessly landed triple lutz after triple lutz. His goal was to cultivate the persona of a clear-eyed, full-hearted intellectual making artwork strictly in pursuit of Truth - the same persona he’s been cultivating since the ‘70s. Only when he talked about the abduction of one of his children by an ex-wife did I feel like he broke character and revealed something about himself or his thought process that didn’t seem to have been strategized to project a very particular image.

His performance exemplified his success. Simply put, Jeff Koons knows how to build a story that validates his work in the eyes of people seeking fulfillment. Most often, this means the wealthy, who have a tendency to turn toward art as an oasis of soulfulness and meaning in what can otherwise feel like a crass and hollow existence. Before they acquire his pieces, Koons gives collectors all the tools they need to be sure that they are truly bettering the world - and themselves - through the act. And frankly, I applaud him for it on a very real level, because he’s figured out how to viscerally connect with his audience.

Waters struck a decidedly different tone. I felt he came across as warm, as funny… and as completely genuine. During a tangent on the topic of Koons’s success, he offered that to him, "Success is two things. One is being able to buy any book you want without looking at the price tag. Two is that you never have to be around assholes.”

The line nearly sparked a standing ovation in the theater. But it also illustrated why Waters has comfortably remained in the same countercultural lane for fifty years, too. Suffice it to say that if you want to build a career in which you can sell art for hundreds of thousands of dollars, let alone $58.4M, you have to spend a lot of time grooming relationships with people John Waters would consider major league assholes. I’m confident that Koons realized as much long ago and tailored his talk track to the task, whereas Waters couldn’t have cared less about the endeavor.

This is not to say that every high net worth individual is a live grenade of deplorable behavior, or that those who fit that description are strictly collectors. (There are offensive personalities working in every sector of the arts, just like any other industry.) But based on the social and political expectations of the art world, any artist who has risen to Koons’s place in the throne room has almost undoubtedly done so by sheathing most, if not all, discriminating personality judgments they could aim at their clientele.

“Sales is the front line of morality” sounds a lot better than “the ends justify the means,” but in this case the two are more equivalent than Koons would ever admit in public. He has spent decades planning and perfecting his narrative, and I suspect he’s done so precisely because he envisioned a career arc that pushed his earnings and exposure to a particularly lofty altitude. And it’s incredibly hard to climb to that height if you’re blasting missiles at every Type A collector, dealer, curator, or rival artist on the way up.

Meanwhile, the talk proved that Waters is smart, funny, and engaging enough that he could absolutely have done the same. But my impression is that he just saw a different endgame than Koons. As a result, he never felt the need to either contort his work into something more palatable, or to devote his energy and resources to shaping a story that could legitimize his work to a more financially elite audience.

He is - and has always been, as far as I can tell - unabashedly and unapologetically his bizarrely quirky self. He didn’t spend his childhood begging his parents to take him to junkyards because of their potential metaphorical embodiment of the human condition; he just did it because he thought they were cool places for make-believe. When you don’t care about crossing over, you don’t need to costume your strangest urges as elaborate cultural touchstones. Don’t try connecting Hairspray to Aristotle any time soon, unless you want John Waters to laugh himself off his chair.

Near the end of the conversation, Waters remarked to his counterpart that he didn’t think that Koons had said one negative word all night, which was rare for an artist. In jest, he then asked the question of the night: “Should we believe you?” The implication was obvious: It would be almost impossible for an honest person in the art world to discuss an entire career without some show of frustration or spite.

Koons tangoed around the topic in typically savvy fashion. But I think the answer to Waters’s question depends on the sense in which it’s interpreted. If asked to take Koons’s many polished answers at face value, then no, I would only genuinely believe a small subset of the words his silver tongue unspooled last night.

But I think such a black and white point of view misses a deeper truth about success in today’s art industry. Every artist needs to hone a pitch, a narrative, and a persona that appeals to their target audience; cement how your work can fulfill them, and you can rule whatever demographic you’ve chosen. Viewed through that prism, there is perhaps no one more authoritative - and thus, believable - than Jeff Koons.

But John Waters is an equally compelling test case for the same idea, the inverse of Koons’s own path. Each one offers a different branded example of success. Together, they embody the basic choice every serious artist must make about her own ambitions: skillful salesmanship for potentially serious profit and a wider reach, or unvarnished honesty for lower likely returns and a niche audience.

Both paths demand a toll. I would urge every artist to think seriously about which resources she’s willing to offer to reach her destination, because the currency accepted on one road is void on the other, and there are no guaranteed intersections after the fork - not even in special interview series.