Why the Myth of the 'Good Billionaire' Is Undermining the Nonprofit and For-Profit Art Industry Alike

This week, how the top of the ladder has taken the art world sideways…

Read Moreshining a light on the shadowy fine art industry

Warren Buffett. Illustration by ValueWalk. Courtesy of Creative Commons License.

This week, how the top of the ladder has taken the art world sideways…

Read More

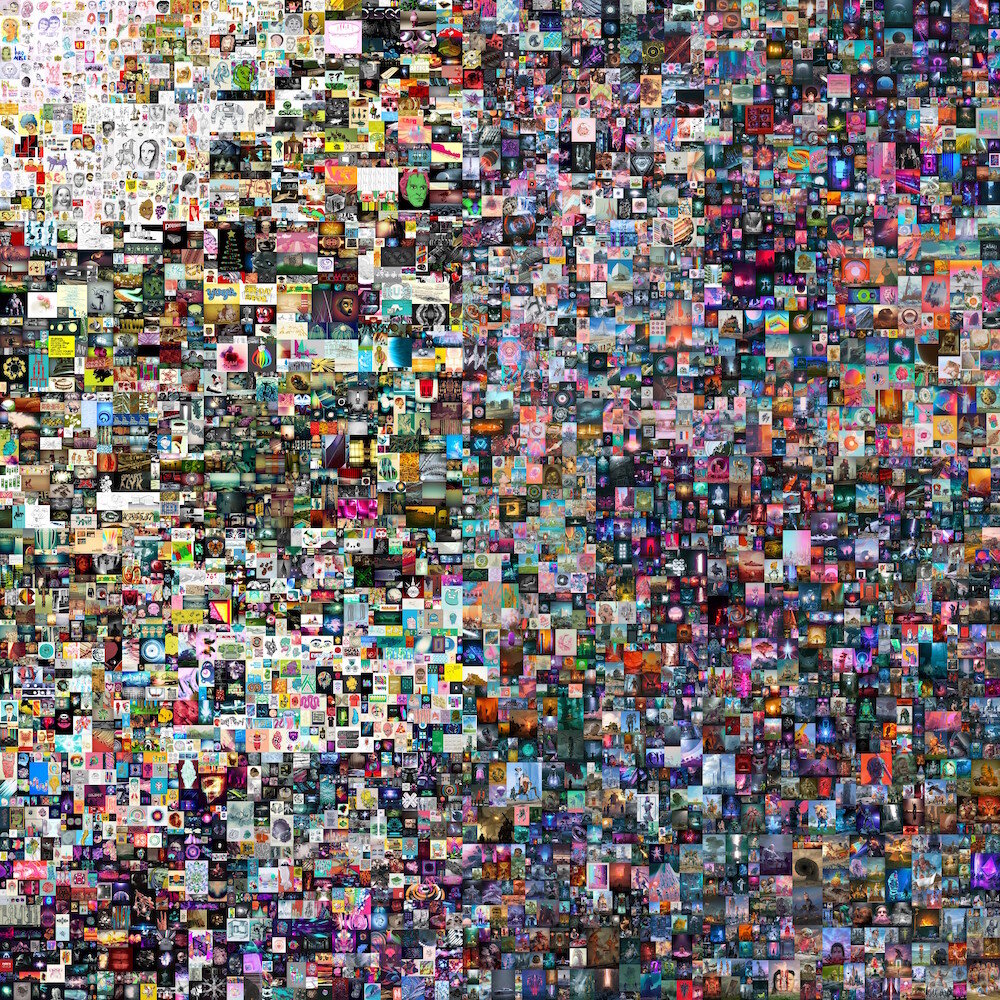

Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days (2021). Image courtesy the artist and Christie's.

This week, finding a way in through the out door…

Read More

George Washington's dentures have a vastly darker backstory than you were taught in elementary school, and I swear it's relevant to the art trade.

Photo by Adam Gerard via Creative Commons License.

This week, crossing the border between theory and practice...

Read More

Rough Trade NYC’s new location at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. Courtesy of Rough Trade.

This week, on changing up without breaking down…

Read More

Jammie Holmes, Wall Street (2018), sold for $100,800 at Sotheby's contemporary day sale in New York in May 2021. Courtesy of Sotheby's.

This week, checking the thermometer inside and outside the art market…

Over the past week, events in the art and finance markets underscored that buyers are only intensifying their interest in speculative assets as rich countries like the U.S. approach full reopening. The similar heat waves gathering in these adjacent economic sectors indicate where the art trade is heading in the coming months—and why market participants should be extra careful not to lose themselves in the swelter ahead.

Let’s start with a standout feature of spring auction week’s New York return. Premier works by several time-honored artists were instrumental in sending Christie’s and Sotheby’s surging north of a combined $1.5 billion in evening and day sales, but so too was a slew of fiercely contested pieces from ascendant talents. In fact, almost all of the most in-demand artists were ‘80s babies. (All sales figures include premiums unless otherwise noted; presale estimates do not.)

Christie’s and Sotheby’s respective evening sales set four personal records for artists under age 40: Nina Chanel Abney ($990,000), Salman Toor ($867,000), Jordan Casteel ($687,500), and Alex da Corte ($187,500). The day sales built at least three more new pinnacles for members of this demo, as my colleague Nate Freeman noted. A Claire Tabouret canvas peaked at $870,000, nearly triple the high estimate; a rare Issy Wood reached $201,600, about 2.5x more than the house’s most optimistic projection; and a Jammie Holmes nude barely missed tripling up its high estimate, landing at $175,000.

Focusing exclusively on shattered records also obscures the fact that buyers chased hard after multiple lots by the millennials above, as well as their sought-after peers. A trio of paintings by Toor all went for more than three times their presale ceiling in Christie’s day sale. Another Holmes painting (this time of the Wall Street Bull) doubled its high estimate at Sotheby's. When the smoke cleared, Amoako Boafo’s portrait of Studio Museum director Thelma Golden changed hands at just under $479,000 despite a top expectation of $350,000. Two paintings by the late Matthew Wong both blitzed through expectations, with In Dreams (2016) finding a buyer at $189,000, almost quintupling its high estimate.

The point is bidders are once again plunging into trench warfare with one another for the right to pay multiples of the primary-market price for works by the most sought-after young artists in the game. Their behavior also tracks with what investors have been up to lately in another realm of high-variance speculation.

If you’ve never before heard of a special purpose acquisition company (known as a SPAC, pronounced like it rhymes with “jack”) you’re not alone... but you’re in a smaller crowd than you would have been a year or two ago. Andrew Ross Sorkin of New York Times DealBook fame called SPACs “the biggest thing in financial markets of the moment” this February—yes, even amid NFT-mania—and their influence among investors has only grown in the time since.

Beyond leaving their imprint on general wealth-pursuit strategies, however, a handful of recent SPAC-related developments typifies the magnitude of the speculative moment we’ve entered. In that sense, they might just be the alarm screaming loudest about the mounting pressure to overpay for upside opportunities across every market right now—including art.

For the uninitiated, I’m going to hand off the task of summing up SPACs to Bloomberg’s Matt Levine via the May 12 edition of his "Money Stuff" newsletter:

The basic way a special purpose acquisition company works is that a sponsor raises a pool of money and has two years to find a company to take public. If the sponsor finds a company, signs up a deal and gets the SPAC’s shareholders to approve it, the sponsor gets rich—typically the sponsor gets shares in the newly public target company worth 20% of the amount raised. If the sponsor does not do a deal within two years, though, the SPAC’s shareholders get their money back, and the sponsor gets nothing and has to foot the bill for the SPAC’s startup and administrative costs.

This is why SPACs are sometimes referred to as “blank-check companies.” By buying into a public SPAC, investors also give its sponsor the autonomy to pursue whatever private companies the sponsor wants with no oversight—or at least, no oversight until the potential merger has been hammered out between would-be corporate partners. SPAC shareholders get an actual vote at that point, as well as retaining the option to simply sell their SPAC stake back on the market if they think the proposed endgame of the SPAC is trash.

(If you haven’t figured it out by now, everyone talking about SPACs loves to say the word “SPAC” as much as humanly possible. Try it now. Kind of delightful, right? I half-believe that the jargon accounts for at least 15 percent of the cash now sloshing around SPACs, especially when you factor in the opportunity to use even more amusing adjacencies like “SPAC-off”—that is, a bidding war between two SPACs courting the same company.)

Investment in the SPAC space has grown so hot and humid over the past several months that it makes the NFT market feel like a climate-controlled museum vault. Consider that NFT sales during the first quarter of 2021 totaled about $2 billion across major exchange platforms, according to a report from blockchain gaming and collectibles database Nonfungible.com. For argument’s sake, let’s add another billion on top of that to give the benefit of the doubt to some significant platforms (primarily NBA Top Shot, Nifty Gateway, and Rarible) that Nonfungible excluded from its report due to implied suspicions over the integrity of their transaction data.

Rounding up like that might not even be especially aggressive, since NBA Top Shot and Rarible have combined to ring up about $672 million in lifetime NFT sales per crypto-analytics site DappRadar.com. In the end, though, it kinda doesn’t matter once you push SPACs onto the scale: By mid-March 2021, investments in SPACs had soared to just shy of $88 billion, according to SPAC Research.

Another way of saying it: Even the most generous appraisal of the NFT trade in Q1 still gives its investor base about 30X less buying power than the investor base for SPACs. Which raises the obvious question: What’s the appeal? And it turns out the answer ties us right back to the art and collectibles market.

SPAC sponsors are sometimes seasoned investors and entrepreneurs whose business acumen could mean something major for investors’ potential returns. (Mega-collector Michael Ovitz and finance goliath Bill Ackman co-sponsor one, for instance.) But many others are fronted by celebrities with… let’s say “highly variable” business credentials. They include superstar athletes (Shaquille O’Neal, Serena Williams, Colin Kaepernick), pop music figures (Jay Z, Ciara, Sammy Hagar), and even career politicians such as former Speaker of the House Paul Ryan.

If some of those names sound a lot like the types you’ve heard cashing in by issuing their own NFTs this year, your pattern-recognition skills are on point. Recall the recent crypto-collectible debuts of Snoop Dogg, Paris Hilton, William Shatner, and NFL tight end Rob Gronkowski.

Which leads us back to auction week, believe it or not. Among the explosive results for sought-after millennial artists, Christie’s also notched a big win for an NFT by model and collector Emily Ratajkowski, whose backstory-rich token brought $175,000 after being offered with no estimate in the house's day sale. But were bidders spurred on more by the perceived long-term value of the underlying digital asset, or by the allure of Ratajkowski’s pop-cultural aura in an overheating market enabled by a historically askew economy?

Celebrity SPAC sponsors invite a similar question: Are most, or even many, of the investors cramming billions of dollars into these vehicles like clowns into tiny circus cars making a sober fiscal decision? Or are they getting sucked in to dumb-money deals by the gravitational pull of the stars at their centers, whatever universe those stars occupy?

As ever, the answers lie somewhere on a long spectrum rather than on one side or the other of a hard binary. But whether the investment (or “investment”) target is a SPAC, a celebrity NFT, or a hotly pursued work by an ascendant young artist, the ferocity of the chase and the velocity of the resulting prices are driven by already-rich people who got much richer during the shutdown, accidental millionaires who lucked up on crypto or meme stocks, or regular Joes/Janes/Jesses putting stimulus money into what they hope will be high-upside, quick-return alternative trades.

Yet the SPAC news cycle has given us the most glaring reasons to think carefully about how much some of these opportunities are worth flying after—and when it’s time to eject from the cockpit.

As you may have noticed in Levine’s explanation of SPACs, there's often a troubling spread between their sponsors’ incentives and their investors’ interests. Sorkin noted in a more recent column that most blank-check firms only prevent sponsors from liquidating their 20 percent ownership stake for a year after the merger closes, and “many include a trapdoor” allowing sponsors to cash out early if the post-deal share price of the SPAC stays more than 20 percent above its initial share price for 20 days out of any 30 consecutive days.

That might sound like a low-probability trigger… until you find out that most SPAC shares start their life trading at $10, meaning that if they top $12 for 20 days, many sponsors can grab the bag and GTFO. Sorkin also backed up fears about the divergence in incentives with data, writing that “in a review of hundreds of deals, many sponsors of SPACs appear to be planning to rush for the exits from the outset, and they rarely invest much of their own money in the first place.”

This curious arrangement has generally worked out much better for SPAC sponsors than SPAC investors. According to JPMorgan Chase, sponsors made an average return of 648 percent on their stakes between early 2019 and early 2021, often by flipping quickly. But shareholders who invested in the same SPACs after they executed their mergers, then held on, made an average return of only 44 percent—worse than the upside of buying into a standard index fund tracking, say, the S&P 500.

The (possible) upside and (more likely) downside were both on view in recent days. DealBook broke news this Monday that a SPAC called Seaport Global Acquisition Co. is preparing to ally with Redbox, the once-ubiquitous DVD kiosk business, at a $693 million valuation. Which could be a brilliant wager on a post-shutdown bounceback for customers hesitant about streaming… or a disastrous bet on an increasingly niche entertainment sector hurtling into a death spiral.

Over the weekend, Bloomberg also reported that five electric-vehicle startups (an especially hot target sector for SPACs) have collectively shed about two-thirds ($40 billion) of their peak market value since going public via different blank-check companies.

And if none of that makes you wary of the froth content in the speculative finance market, let me close by noting Friday's executive shake-up at New Jersey’s Hometown Deli, the unassuming sandwich shop that stymied investment analysts for weeks by pairing $40,000 in sales since 2019 with a mysterious $100 million valuation (not a misprint!) and institutional shareholders including Duke and Vanderbilt universities. The puzzle was finally solved in late April, when FT's Mark Vandevelde learned Hometown's holding company is actually… a pseudo-SPAC designed to shuttle an Asian company onto a U.S. stock exchange ASAP.

To be clear, I’m not saying that winning a Salman Toor at auction last week is identical to buying shares in a Garden State deli sliding through an SEC loophole. But I am saying that market participants are showing all kinds of signs that they’re chasing returns at full throttle. No matter who you are, it’s worth asking how that race affects your own behavior on the road ahead.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: Sometimes you get to ride the bull market to glory, but eventually you'll just get the horns.

Image by Diegosegura.me. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, via Creative Common Attribution Share-Alike 4.0 International License.

This week, asking which advances qualify as genuine progress…

Read More

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night (1889).

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, via the Gnu Free Documentation License and Creative Commons 4.0 International License.

This week, trying to distinguish between a lifeline and a live wire…

Last week, I started hearing chatter about a new twist in the art world’s crypto-saga: some leaders at major U.S. museums had begun quietly exploring the possibility of selling NFTs of some of their most famous artworks to fundraise after more than a year in shutdown hell. But while the proposition might technically keep institutions clear of the public-relations wildfire that is deaccessioning, this alternative route might actually lead them straight into an even worse disaster.

Now, there is a lot going on in this thought experiment, so let’s begin with the tech side. If you’re still only in the shallow end of the crypto pool, it might be a little jarring wrapping your head around a non-fungible token for a physical object. After all, the nitroglycerine in 2021’s NFT explosion has largely been digital media. But an NFT is really just a claim ticket to an asset (meaning, an artwork). And while the NFT lives on the blockchain, the asset could be physical.

This isn't a brand new idea. Between about 2014 and 2018, a number of startups emerged that were primarily dedicated to creating on-chain title registries for old school, off-chain art like paintings and sculptures. (It was a whole thing. A few of them have kept on keeping on.)

But if there was any in-depth discussion about the idea of monetizing NFTs for works in institutional collections at the time, it got nowhere near the mainstream. I suspect that's because there wasn't much demand for even the for-profit use cases, let alone something else.

Then 2021 started. Yes, NFT prices are still wavy, the overwhelming majority of the money is still going to a select few artists, and most of the tokens ringing up thunderous prices still correspond to strictly digital assets.

But there is some real demand for NFTs certifying ownership of physical assets. For example, of the 10 tokens designer Andrés Reisinger sold in minutes for $450,000 this February, five were to validate tangible pieces of to-be-fabricated furniture. The cocktail of real desire and real wealth can make anything possible almost overnight in every market. So why not museum-sanctioned NFTs of some of history’s greatest artworks?

Since the pure tech side of museum-collection NFTs is feasible, the next questions to explore are whether they would be feasible from a legal, regulatory, and governance standpoint. The short answer appears to be “yes” as long as certain conditions are met.

In the simplest and most lucrative version, the actual painting or sculpture would first need to be owned free and clear by the museum. But if it isn’t old enough to be in the public domain, leadership would need to secure permission from the artist’s estate to mint and sell the NFT. Doing so would be delicate, complicated, and probably not cheap; due diligence, negotiation, and compliance take real resources. But you don’t need to be Isaac Asimov to be able to imagine a world where it happens.

In fact, museums actually navigate a lot of these rapids just to sell posters and coffee mugs emblazoned with their most famous paintings. Setting aside philosophy and ethics for the moment, an NFT of, say, Starry Night would be just another avenue for MoMA to monetize the work without upending the underlying property rights: the Fondation Vincent Van Gogh retains control of the copyright, and the museum retains controlling ownership of the object.

“Controlling ownership” is key here. The only scenario in which plutocrats might get fat-check excited about an NFT is if it certifies a claim to the actual artwork, not some “unique” digital reproduction of it. But it can’t be a majority claim, either, or else the buyer would have legal grounds to march in like Darth Vader with a shock force of art handlers and grab Starry Night off the wall to take home.

This means any museum NFT would only confer minority ownership of the work. This is not actually as foreign as it sounds, because U.S. museums have been accepting so-called partial gifts for generations.

In this structure, donors agree to transfer, say, 10 percent ownership of a painting to an institution every year for a decade, with proportional tax benefits along the way; at the end of this span, the work fully enters the collection. To ground the benefits in reality, if you’ve ever marveled at the 53 Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works comprising the Met’s Annenberg Collection, or sunk into Paul Cézanne’s Boy in a Red Vest at MoMA, you can thank partial gifts for the experience. The same can be said for hundreds of other bravura pieces at institutions around the country.

To my understanding, museums could essentially invert the regulatory and governance principles that enable them to accept partial gifts to sell partial ownership of works in the collection via NFTs. On the surface, then, it seems like this strategy might be the best of both worlds for cash-strapped institutions: all the financial benefits of deaccessioning, but without actually losing control of the painting.

There is one big caveat, though. In theory, every one percent of fractional ownership translates to the right for the recipient to actually possess the piece for the same percent of the calendar year, meaning, 10 percent ownership equals 36 annual days of control. But in practice, museums have usually been content to let fractionally gifted works stay with the donor until the deal’s conclusion.

I suspect institutions would want to build on that convention by structuring the (smart) contract so that an NFT’s buyer acquires no right to partial possession of the underlying piece—ever. Even the risks of schlepping Starry Night a few blocks north to a Billionaires Row penthouse for 36 days a year are too high for a museum board to stomach. Forget about selling two percent ownership to an Emirati royal and having to slide one of civilization’s greatest artistic achievements onto a private jet for an annual one-week trip.

Could this detail be a dealbreaker? Well, that’s the first of what I see as the vital questions about this concept’s ultimate value to struggling museums.

Since so much of the NFT boom is being driven by the allure of intangible bragging rights, not the possession of objects, my hunch is that demand for the tokens would not be affected much if patrons understood the underlying masterpieces would stay locked inside the institutions forever. But other factors might, in the eyes of New York University’s David Yermack, an organizational economist who has done pathbreaking work on both museum governance and crypto.

“I think demand for NFTs is driven by tech-savvy people,” he said. “They may not appreciate an Old Master painting in the same way as an 80-year-old billionaire would.”

Anecdotal evidence supports Yermack. It isn’t just that the bulk of top-selling NFTs correspond to digital-only assets. It’s also that the artists on the receiving end of all that crypto-wealth have generally built careers entirely outside the artistic establishment.

When Christie’s decided to auction its first NFT, it didn’t latch onto Damien Hirst’s forthcoming blockchain opus; it partnered with Beeple, whose name carried about as much weight with traditional mega-collectors as mine would at Buckingham Palace. Yet that choice rewarded the house with a $69 million milestone. I think every art lover (myself included) should level with themselves about the very real possibility that Beeple may mean more to the crypto-wealthy than Vincent van Gogh.

Another important factor pumping up profits in the NFT market is the economy of fame. Demand has propelled tokens of a LeBron James highlight video to $208,000; Twitter founder Jack Dorsey’s first tweet to $2.9 million; and whistleblower Edward Snowden’s photomontage self-portrait to $5.4 million, to name just a few. Christie’s next big NFT sale on May 14 centers on a backstory-rich photo of model and collector Emily Ratajkowski. There's no guarantee that an NFT for what we, in the niche-within-a-niche art world, consider to be masterpieces would bring a similar windfall to the museums that own the paintings.

But I agree with Yermack that the uncertainty shouldn’t hold back an institution that feels compelled to find out this way. “My advice to museums would be to give it a whirl, and see if you can develop a market—but do it quickly.” Despite some recent turbulence, crypto is still having a moment, and that moment may be fleeting.

Yet there’s more to the equation than just economics and timing, too. Amy Whitaker, a professor of visual arts administration at NYU who began researching blockchain in 2014, told me she has been informally approached by museums about how they might leverage NFTs. Her opinion is that deaccessioning is actually a less fraught option than crypto-fundraising from works still held by an institution.

“I can see how the latter looks like free money to people, but it’s kind of like fracking your collection: there are a lot of knock-on or second-order effects that are hard to think through ahead of time,” she said.

One institutional curator who works with digital art echoed Whitaker’s thoughts. They felt that the entire meaning of “stewardship”—one of the responsibilities forming the nucleus of any museum—would need to be rethought in order to coexist with NFTs of institution-owned pieces. (By the way, they too had heard chatter about museum leaders exploring the prospect of trying this.)

Basically, the point is that it’s fine to relinquish your stewardship entirely through (rulebook-observant) deaccessioning, and it’s fine to hawk gift-shop reproductions of a work you’re still caring for. But it’s something else entirely to monetize the actual work while it keeps hanging on the gallery walls.

In other words, instead of being the best of both worlds, this scheme might actually be the worst one yet. So where does that leave us?

To me, the most salient point of all is the only one on which all the people I spoke to agreed. Even Yermack, who adopted the most supportive stance on museum-offered NFTs, still saw them as insufficient to rescue U.S. museums from the historic crisis they’re now enduring. In the best case, NFTs still probably won’t raise truly difference-making money from the people who care most about art institutions, yet they’re guaranteed to magnetize at least as much controversy as deaccessioning.

But to me, instead of shrinking back to the status quo, we need to think bigger. Museums are not just under duress from an external catastrophe. They are also suffering from structural problems in fundraising, governance, and even discourse that have been intensifying for decades.

Yermack, who has published influential studies of board governance as far back as the '90s, argued that “nonprofit boards are very often dysfunctional, and never more than in art museums.” Research has found that, across industries and across the for-profit/nonprofit divide, the most effective organizations are led by boards that top out at less than 10 seats. Most nonprofit boards, however, typically count 50 to 100 trustees, which makes them “not really boards at all, just incubators for potential donors." If the hollowed-out budgets from this past year’s crisis haven’t called into question how well those incubators are working, I don’t know what would.

Whitaker also thinks museums need to be vastly more transparent about their operations. Inside, they may be mostly white cubes, but from outside they mostly remain black boxes. The public only hears about budget shortfalls, attendance numbers, and whether ticket prices are going up. But what does it mean for museumgoers if an institution has to spend 70 percent of its unrestricted funds to keep staff employed during an epic lockdown? What is the institution doing day-in, day-out to represent the community and engage its needs outside of its programming?

As Whitaker put it, “You figure out in a crisis how much good will you’ve generated.” Personally, I haven’t seen a lot of people leaving care packages at museums’ front entrances during the past 13 months, and I think that means something.

And finally, yes, there’s deaccessioning. I think there’s tremendous merit to doing it on a much grander scale. But details of that expansion matter too, and it seems impossible to have a conversation about what they could be without instantly being dragged into a no-holds-barred flame war.

Would it really be a crime against nature if deaccessioning proceeds were expressly put toward the endowment, or paying museum staff a living wage? What if a museum director thinking laterally about deaccessioning weren't automatically assumed to be a soulless bureaucrat who can’t wait to sell every painting with a healthy appraisal to stock up on toilet paper and pre-pay 12 years of HVAC bills? And what if “serving the public trust” could actually mean something more community-focused than clutching onto a massive art collection as it plunges an institution, its staff, and its rank-and-file visitors over a financial cliff?

I’m not saying I have the answers. But I am saying we need to start from square one to try to find them, beginning with the acknowledgments that museums have a hard job to do, and those of us who care about them should have more in common with each other than the current debate positions us to recognize.

One thing I’m sure of, though, is that issuing NFTs won’t save museums. And the more time we spend looking at them, the less time we spend looking at other big ideas that might.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: the main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing.

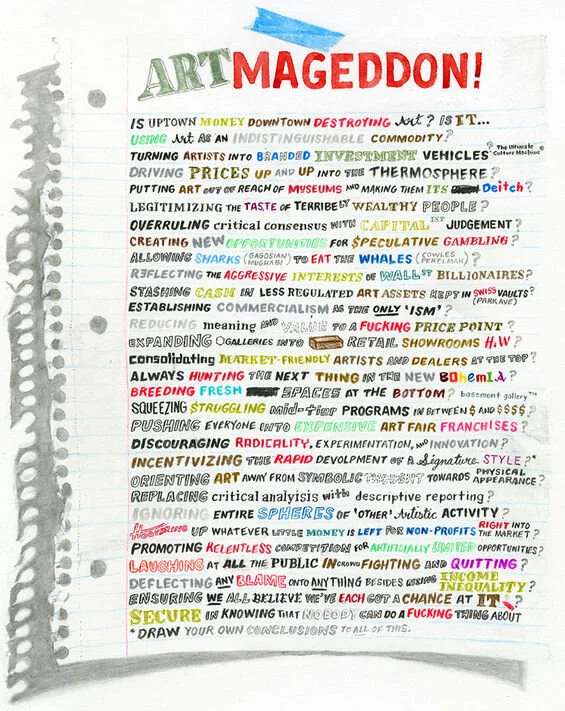

William Powhida, Artmageddon (2013). Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters.

This week, asking when enough is enough…

Read More

Screen grab of the NFTheft page showing details of the "sleepminted" NFT.

This week, clawing down another art-tech rabbit hole…

Read More

Photo by David Saddler. Courtesy of Flickr via Creative Commons License.

This week, anticipating a new clash between collectors and the taxman...

Read More