Free Love + the Dark Side

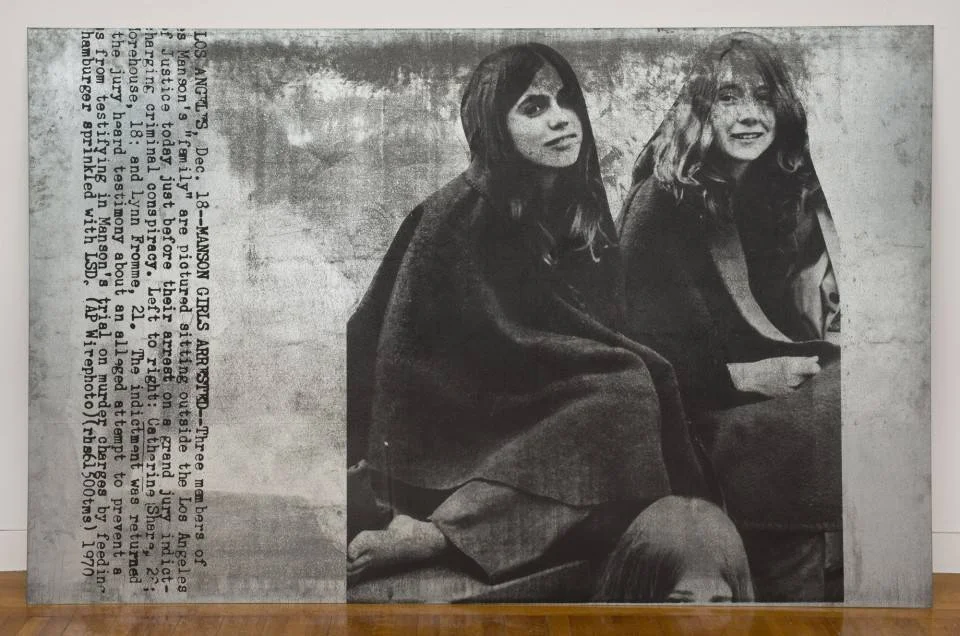

If we've learned nothing else from the study of cults and communes, we've learned that an "all are welcome" ethos can lead to unexpectedly grim places. David Koresh's Biblical egalitarianism eventually triggered a disastrous federal raid in Waco. Jim Jones's gospel of inclusion later gave morbid meaning to the phrase "drinking the Kool-Aid." And Charles Manson almost single-handedly ended the swinging '60s by using free love to pry open the door to hell.

What does this have to do with the art market, you ask? In a New York Times feature last week, Lori Holcomb-Holland surveyed the many ways in which Christie's, Sotheby's, and Phillips are chasing the cool to try to attract young collectors (or as she refers to them in her lede, the "deep-pocketed, skinny-jeans crowd"). Anyone with an imagination and a fingertip near the pop cultural pulse can likely guess some of the specifics: partnerships with famous rappers and models, invite-only parties and celebrity-chef dinners, services and brand presences increasingly centered online. The list goes.

However, one of the houses' less obvious strategies is to begin building special sales around unifying curatorial concepts rather than traditional time periods or genres. The trend jumped off last spring with the runaway success of Christie's "If I Live, I'll See You Tuesday," an auction organized by specialist Loic Gouzer around edgy work meant to "capture the raw angst" of a "generation of rich embryonic collectors," as Carol Vogel phrased it at the time. And Holcomb-Holland writes that the idea has only gathered strength in the auction sector since:

Gone are the days when collectors, by and large, focused on just one period of art. Themed sales that unite around an idea, rather than around a specific genre or era, are more common in the midseason but are increasing in the larger November and May sales.

“New collectors today are coming into the market collecting in at least five different categories,” [Christie's global president Jussi] Pylkkanen said. “They want to put Picasso with Basquiat, they want to put Giacometti against de Kooning, Cézanne against Mondrian and against Minimalist artist of the postwar period. They collect very broadly and in interesting ways. Lots of juxtapositions.”

To me, this looks like yet another way that consumers of fine art are following the same path as consumers of mass media. Even 15 years ago, it was still common for people to silo their taste by genre, especially when it came to music. Punk fans shunned hip hop, country enthusiasts lived on a rustic island surrounded by a sea of whiskey, and classic rock aficionados tended to act as if they alone had discovered fire (and should be treated as such).

Fast forward to today: Largely thanks to the Internet and social media, anyone under the age of 40 who only listens to one type of music is basically an alien. Authors and readers alike treat the categories "fiction" and "nonfiction" as suggestions at best (and meaningless at worst). And the prototypical American TV schedule is an eclectic mix of prestige cable dramas, satirical news shows, gonzo reality series, and more.

In light of this crockpot approach to culture, it should come as no surprise that Millennial fine art buyers are refusing to segregate their acquisitions by time period, genre, or medium. This is indisputably good news for players with a broad historical reach, such as museums, well-resourced secondary market dealers, and yes, auction houses. But whether it's good for living artists and primary market gallerists is a much hazier question.

The optimistic view is that collectors who once might have restricted themselves to the works of ghosts now feel inclined to buy into the land of the living, too. This shift broadens contemporary artists' and gallerists' client base, increases the overall pool of available money, and grows their returns through scale. In short, the more, the merrier.

However, when strong consumer bias evaporates, that means contemporary collectors and gallerists alike face much fiercer competition than ever before. It was hard enough to make a sustainable living via art sales even 10 years ago, when one only had to worry about beating out rivals who were drawing breath in the same particular niche of the market. But if young collectors are truly genre- and era-agnostic, as the Big Three auction houses now believe, then contemporary artists and gallerists have to beat out past greats as well as present ones. Picasso and Modigliani are much friendlier figures when they're not clawing their way out of the grave to eat your lunch.

It may still be too early to tell which way the wind ultimately blows on this issue. Trends, by definition, don't always last. But I for one am keeping a wary eye on the weathervane. Because as admirable as young collectors' Free Love mentality may be from the standpoint of art historians, it could have a Manson-like dark side for practicing artists and their representatives. The wider that would-be benefactors open their arms to the field, the smarter it is to beware of what comes next.