Garcetti's Goldilocks: The Challenge of Privately Funding Public Art

The Los Angeles Times reported on Tuesday morning that mayor Eric Garcetti met with 100 local “arts leaders” to begin a wide-reaching metropolitan re-branding effort. The centerpiece of Garcetti’s vision seems to be an ambitious series of nonprofit public art projects - all yet to be determined - that could help further shift the city’s image from celebrity live-work habitat to flourishing, diverse hothouse for high culture. In his own words, he wants Los Angeles to become known as “where creativity lives."

It’s not clear to me if that phrase is city hall’s official slogan for this embryonic campaign, or just a particularly snappy moment from Garcetti’s prepared remarks. What is clear is that he and his team will be strictly backseat drivers on the initiative. The mayor used the meeting to announce that he hopes to manifest this grand dream via crowd-sourcing ideas for the projects from his invitees. He urged them to think big. Instead of just envisioning how they each might be able to get funding for a program or project bound to their own specific niche of the arts, Garcetti asked his guests to step across the borders separating disciplines and consider more more far-reaching, inclusive, and collaborative concepts.

After this rousing and admirable intro, though, the other shoe crashed through the rafters with the velocity of a downed satellite. Garcetti announced that these ambitious future projects would not be accompanied by additional public funding. Mustering a level of spin that would make Rafael Nadal jealous on clay, Garcetti declared that "Los Angeles can do a better job promoting the arts than by subsidizing them.” The mayor then followed up that dynamic English by offering his guests a tidy solution: “We have a tremendous amount of wealth in the city that’s waiting to be asked [to fund the arts] in the right way.”

And there you have it. To continue LA’s maturation into a global arts capital, all that’s needed are a few good sales pitches aimed at the city’s overflowing population of financial elites. Easy recipe, right?

Well, not exactly.

Let’s cycle back to the setup. It’s no secret that the city of Los Angeles is strapped for cash. Nor should anyone be surprised that arts funding is lower than priority 1A on the metropolitan budget of any major American city. Those points alone are enough to divert the focus of a serious philanthropic capital campaign toward the private sector. But there’s truth to Garcetti’s point about the attractiveness and viability of private funding on its own merits, too. I’d guess that individual and corporate donors have been a more robust, fulfilling source of nourishment for the arts than any level of US government probably since the demise of the Works Progress Administration. If nothing else, the mayor deserves a little credit for being honest about the initiative’s fiscal constraints and his own limited vision for the types of projects it would need to succeed.

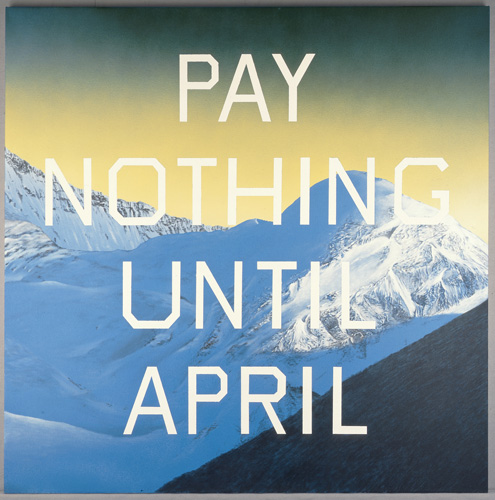

However, the journey from concept to reality is far more nuanced and challenging than his remarks suggest. Securing private funding for public art is less of a casual road trip and more of an expedition up K2. I suspect Garcetti is genuinely unaware of it; he seems to know the topography of the art world about as well as I would know the angles behind the scenes of a city council meeting. But unfortunately, that doesn’t flatten out the mountain.

Two factors complicate the road ahead for the mayor’s campaign. The first of them is a favorite topic here on The Gray Market: personal branding.

Whether they are individuals or corporations, deep-pocketed private donors start every year with incentive to support non-profit projects. Yet the reason goes beyond tax benefits. Benefactors enjoy the prospect of receiving credit for their philanthropy - especially credit that’s obvious, public, and permanent. More broadly, “doing good” in any form becomes more appealing to us as a species when we get to advertise that we’re doing good. As economists Steve and Alison Sexton demonstrated, the Prius has been vastly more sought after than equally green hybrids from Toyota’s competitors almost entirely because it has a unique, unmistakable shape. Compare a Civic Hybrid to its sister on the all-fossil-fuels diet, and the only difference you’ll see is a name plate or decal on the rear that signifies its environment-friendly identity. That’s no way for a hybrid owner to garner applause for her Earth-conscious decision-making - hence, the demand for the one hybrid that can be recognized with even the most casual glance.

The Sextons dubbed the Prius popularity phenomenon “conspicuous conservation,” a play on “conspicuous consumption.” Though I don’t have a clever turn of phrase to describe it this second, a similar principle applies to funding nonprofit projects. Donors like to be able to attach their brand to public goods that people appreciate. In fact, they like it so much that they’re often willing to pay for the privilege. So far so good for Garcetti’s vision, right?

The key, though, is in the reception of what’s being funded. Sponsor what’s deemed to be a great public arts project, and the glow of positivity from the visiting masses reflects back onto you or your corporation. But what if you misjudge? What if you instead sponsor something that people ignore - or worse, something that people truly hate?

Although the patron was a government bureau rather than a private donor, the infamous case of Richard Serra's Tilted Arc is a ghost that forever haunts the realm of ambitious public installations. New Yorkers were so outraged by the confrontational sculpture that the project’s funding source, the General Services Administration, bowed to public pressure and agreed to remove the work to save face. This decision set off a protracted legal battle with Serra; the litigation ended with the piece being de-installed and transported to a storage facility in Maryland, where Serra deemed it would stay unless and until it can return to the site it was conceived to fill (and from which it was forcibly removed). Since there is zero chance of such a homecoming, the work will be left in the dark to rust until the sun extinguishes itself.

Tilted Arc was an absolute worst case scenario. But worst case scenarios are exactly what donors consider when presented with the opportunity to fund a major public art project. It takes a courageous patron to risk the possibility of a toxic crowd reaction, let alone withstand the real thing should it come. That makes any never-before-seen public art concept an inherently thorny proposition for would-be givers.

So how do Garcetti’s cultural proxies get around this problem? Allow me to draw another analogy. Astronomers concocted a term to encapsulate the set of conditions needed for a given pocket of space to support life on a planet hovering inside it. They call it “the Goldilocks zone.” (OK, technically they call it the “circumstellar habitable zone” in the lab, but they use the other term when they’re addressing the rest of us.) I’m simplifying the definition here, but the general idea is that said planets must have just the right amount of atmospheric pressure and must absorb just the right amount of radiant energy from a nearby star for water to remain there. Not too hot, not too cold. Similar to the world we know, and yet just different enough that the possibilities become tantalizing.

There’s a Goldilocks zone for public artworks and non-profit giving, too. A project only has a fighting chance for private funding if it’s both “safe” and substantial enough that a private donor would want to attach her name to it, but not so controversial or monumental that it raises the specter of public backlash or unattainability.

This is no easy feat. Garcetti unwittingly revealed as much in the examples he spooled out in his remarks on Tuesday. They included “cultural attractions at [LAX] and at Metro rail stops,” the facades of city buses, and the structures of cell phone towers. I suspect that all of these would be relatively hard sells to the types of high net worth individuals and corporations that the mayor implies are crucial to the initiative’s success. How excited is anyone with a sterling reputation likely to be about sponsoring the paint job on a bus, no matter how creative it may be? As an example, twelve LA Metro buses received the artistic treatment from John Baldessari as part of a larger campaign by the nonprofit Los Angeles Fund for Public Education last year. They were set to operate for about a month, then slough off their temporary skin and revert to their typical look. The Baldessari fleet seems to have gone quietly into that good night as scheduled; I can’t find evidence of any groundswell of support for it to remain in operation. Does that suggest this level of public project sufficiently stimulates donors? More importantly, does a collection of artist-branded buses really move the needle on the city of Los Angeles’s reputation as an arts powerhouse? Both ideas feel dubious to me.

Garcetti’s last specific idea demonstrated the opposite problem. He invoked the Statue of Liberty and asked rhetorically why LA didn’t have an artwork of similar magnitude at its own bustling port. In some ways, I would argue that this is actually the most viable of the possibilities he presented at the podium; at least it dreams big enough to energize potential donors. But as Mike Boehm of the LA Times pointed out in his reporting on the meeting, Lady Liberty was funded by the entire tax-paying population of France. Certainly a consortium of donors could bankroll such a massive undertaking (assuming no mega-wealthy collector wanted to permanently stamp her solo imprint on the city). But I say “undertaking” for good reason. The larger and more complex the project, the higher the probability of its failure, death, and demolition. That’s likely to temper the enthusiasm for gigantic public artworks at least as much as for minuscule or unglamorous ones like anonymous Metro stop sculptures.

All of these pitfalls concerning a project’s identity feed into the second major complication to Garcetti’s initiative: competition. The fact is that there are a plethora of options for donors’ philanthropic urges. Here in LA a few years ago, mega-collectors Lynda & Stewart Resnick blasted a firehose of money into LACMA for a new exhibition space on the museum campus, known forever after as… you guessed it, The Lynda & Stewart Resnick Pavilion. This is the most extreme donor branding you’ll see in a pre-existing museum. But there are several steps down from that apex within the same institution. Next time you walk into a museum anywhere, take a look around at how many items are emblazoned with the name of a generous sponsor. From the actual individual galleries to the special one-time exhibitions and beyond, practically everything is philanthropically branded.

Of course, art museums are hardly the only venues for this phenomenon. College campuses. Parks. Historic movie theaters. Sports arenas. Scholarship funds… I could spend the rest of the day expanding the list. All of these are much safer investments for a branding-conscious donor; it’s almost impossible to enrage the citizenry by sponsoring new additions or renovations to them. If you’re a wealthy patron interested in philanthropy, why would you expose yourself to the risk of an unknown quantity like a public art project when you can instead attach your brand to a sure thing?

There’s another dimension to the competitive element, too - one confined to arts investment itself. Monumental visual projects aren’t limited to philanthropic endeavors or publicly accessible sites anymore. Today, ultra-high net worth art enthusiasts are scratching their most grandiose creative itches by spending on ambitious projects over which they maintain complete authority and ownership. There are innumerable structures and large-scale commissions tucked away on private property the world over that few among us will ever experience firsthand, from James Turrell Sky Spaces to entire private museums. The closest we’ll ever come will be the occasional photo spread in, say, a Wall Street Journal lifestyle feature on the private screening rooms of Hollywood.

Of course, for the uppermost financial tier of collectors, bankrolling their own pricey private commissions doesn’t necessarily preclude them from simultaneously supporting public art. But it does raise the question of how much they are open to spending at any given time - while for the tier of collectors below them, multiple projects may simply be too great a burden to bear. Call me a cynic if you will, but I tend to believe that, if confronted with the ultimatum of funding the greater cultural good of Los Angeles or funding their own private Shangri-La, most targeted donors will default to the latter.

Pushing philanthropic projects is in many ways the most difficult sales job in the contemporary art world. If LA’s great rebranding effort is to prevail, its leading cultural lights must be incredibly savvy about the identity and scale of the projects they pursue, deeply knowledgeable of their charitable competition, and powerfully convincing when it’s time to make their pitches to the “tremendous amount of wealth in the city.” Otherwise, mayor Garcetti’s campaign to transform LA into “where creativity lives” may lose hold of the slope and plummet into the abyss well before it even spies the mountaintop.