Is Deaccessioning the Devil?: Part 1

If you follow art news, deaccessioning has been a hot topic in the past year - most prominently as a part of the fiscal and ethical morass that is the city of Detroit’s bankruptcy. In standard English, “deaccessioning” means the official removal of an owned artwork from a museum’s permanent collection, usually for the purposes of sale. Months passed with the very real possibility that the Detroit Institute of Arts’ might be coerced into deaccessioning multiple works to raise funds to help resurrect the city from the rare hell that is chapter 9.

That possibility appears to be growing more remote by the day. An announcement came Wednesday that the city is closing in on a settlement deal that could get Detroit off the mat while keeping the museum’s holdings off limits, and yesterday judge Steven Rhodes questioned whether selling off parts of the collection would even be legally allowable.

But no sooner has that sordid episode begun to lose power than another potential deaccessioning scandal threatened to surge ahead. Just last week, LA’s perpetually troubled Museum of Contemporary Art announced the hiring of Philippe Vergne as its new Director. Despite occupying prestigious positions at highly respected institutions like New York’s Dia Art Foundation and Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center, Vergne’s body of work displays a few distressing deformities, particularly at Dia, whose Directorship he departs for MOCA. They begin with his inability to jump-start the foundation’s return to Chelsea and progress to accusations of negligence (or at least seeming disinterest) regarding the maintenance of Robert Smithson’s land art masterpiece Spiral Jetty, arguably Dia’s most important holding.

Yet Vergne’s critics reserve their flamethrowers’ hottest setting for his 2013 decision to deaccession and auction several renowned blue chip works from Dia’s (apparently not-quite) permanent collection. The move was intended to amass funds for Dia to acquire new works to replace the exiles, including a handful of pieces then on loan to the institution. Despite pressure - both public and legal - from Dia’s own founders, Vergne saw the process through, eventually netting the foundation a reported $38.4MM via Sotheby’s.

Only a week after word leaked about Vergne’s union with MOCA, skeptics like Tyler Green (scroll down to his comments on January 15th if you click through) of Blouin Art Info / Modern Painters and Lee Rosenbaum now look prescient, especially in raising the specter of a west coast sequel to Dia’s deaccessioning scandal. So prescient, in fact, that if this was late 17th century Salem they would probably both be on trial for witchcraft today. Vergne made comments in an LA Times interview on Tuesday that hinted he might consider deaccessioning works from MOCA’s (still to-this-point) permanent collection if he thought the move could benefit the museum’s long term outlook - an innuendo for which Green blitzed Vergne in a post Wednesday.

Should the possibility of deaccessioning become real, MOCA and its new Director had better armor themselves for a much heavier assault from a much more pluralistic force. Deaccessioning is still almost universally regarded as a deplorable tactic in the art world - a lazy, unethical shortcut to a result achievable by cleaner means. Think of it as the museum equivalent of a drone strike that sacrifices innocent bystanders for the sake of assassinating an alleged high value target; it gets the plan’s architects what they want, but in the darkest and dirtiest possible way.

Still, the brewing controversy got me thinking… Does deaccessioning deserve to be vilified? Or, if evaluated on economic terms, is there a viable argument that it could seriously benefit museums willing to withstand the opposition’s onslaught of criticism?

To pursue this thought exercise, we have to do what economists do: namely, remove the entrenched morality, ethics, and emotion slanting the issue so that we can look at the facts and incentives with a calculating robotic eye. Once we’ve done that, we can re-combine all the components and see where they actually align.

The first step, though, is understanding the outrage. The core of the anti-deaccessioning movement hinges on art museums’ role in society. They are the traditional caretakers of culture; their mission is to tell the story of art history. They accomplish that mission by collecting works of merit, safely maintaining them for posterity’s sake, and thoughtfully exhibiting them for the public good. Deaccessioning, the argument goes, ruptures the entire bond between cultural institutions and the citizens they are supposed to serve. By selling off a previous regime’s acquisitions to bring in new work of her choice, a museum’s Director betrays the very mission statement she’s been hired to uphold. The museum ceases acting like a museum and begins acting like a private collector. Since private collectors are beholden to no interests other than their own, nothing in their holdings may be sacred - whereas, in theory, everything in a museum’s holdings should be.

I happen to agree with that perspective - at least, in principle. But are there circumstances in which deaccessioning could strengthen an institution without actually breaking faith with the ethical ethos we just covered?

Vergne infamously defended the Dia auction at the time by claiming that a museum could not be a “mausoleum.” He traded in that analogy for a slightly smarter one when looking back on the incident in the aforementioned LA Times interview. There, he stated that museum professionals are “a little bit like gardeners - there is no growth without pruning.” If we haul this statement onto the autopsy slab, I could argue that there’s merit to it. However, it’s merit that materializes only under a very strict set of conditions.

Imagine you’re the savviest, most forward-thinking museum Director in the world. You’re hired to take over a lauded institution that’s fallen on hard times. In examining their permanent collection, you find multiple works that your knowledge of art history and the art market have convinced you are secretly active volcanoes. Sooner or later, they are going to erupt in an unholy storm of ash and magma that will scar whomever is holding them when it happens. Afterwards, they will be effectively worthless. You ardently believe this on the basis of evidence that other scholars, gallerists, and auctioneers have ignored. If you had made this discovery about a set of assets in the financial realm, the best thing to do would be to find a way to short them. The closest equivalent in the art world, though, would be to deaccession them immediately. Sell them off now before the rest of the market catches on. Get a favorable return - or any return at all - on a sunk cost investment that you know will go to zero. Assuming you’re right, history will vindicate your decision and extinguish the criticism lobbed your way when that decision was made.

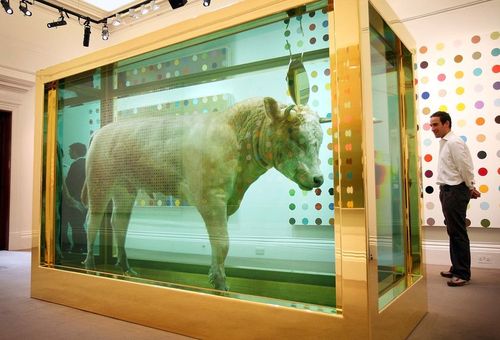

The problem is that it’s almost impossible to identify works that would fit these criteria. The closest thing to an example that I can find would be the precipitous decline in value of Damien Hirst. But even here we should be cautious. There is a difference between the art world concluding that Hirst’s work was overpriced between 2005 and 2008, and concluding that his work has no value whatsoever, in the style of a subprime mortgage-backed security. Say what you will about the quality of his output in comparison to the acknowledged masters, but I find it dubious to suggest that fifty or a hundred years from now, the consensus will be that Hirst simply did not matter in the arc of art history.

True, we may not like what he indicated about our culture in this era. That, however, is beside the point. If a museum’s job is to tell the story of art’s development over time, then Hirst is still a far cry from the hypothetical Big Short scenario I just outlined in the previous paragraph. His work brings value to the institutional mission of a major museum; that value just may not be equivalent to the numbers on the wire transfer sent to acquire it. Overpaying, even drastically, to bring a culturally important work into a museum’s collection is not sufficient justification to deaccession it - not if that process would leave a hole in the art historical narrative that the museum exists to relay.

The only defensible scenario might be if the institution could deaccession a Hirst work and acquire an equivalent one at a lower price than what they just sold their exile for. But this is unlikely. Entire categories of an artist’s work - say, animals preserved in formaldehyde - tend to deflate across the board. Even if they didn’t, what sense would it make to sell a more valuable work only to turn right around and acquire a less valuable replacement? The realistic best case scenario would mean robbing Peter to pay Paul, and the worst case would mean taking two losses over one.

The only other potentially viable argument for deaccessioning has to do with diversifying the museum’s collection. Among the lots offered by Dia in 2013 were ten John Chamberlain sculptures, out of a total of 100 Chamberlain works owned by the foundation. A deaccessioning defender might argue that it makes little sense for the institution to be so flush with pieces by one artist, even one with Chamberlain’s sterling reputation. Selling off a mere 10% of their Chamberlain holdings would give Dia a war chest with which to expand their portfolio in exciting new directions, right?

Maybe. But not without some potentially serious collateral damage. Like gallerists, museums thrive on branding. Their distinctiveness can stem from any number of sources. The Dallas Museum of Art, as I’ve written before, is building an identity based around technology and visitor interactivity; my hometown Cleveland Museum of Art is renowned for its Medieval collection; the Art Institute of Chicago is celebrated for its Monet holdings, with over thirty works crowned by one of his iconic Water Lilies paintings. There is value to a museum in collecting deeply instead of just broadly. Owning 100 Chamberlain pieces is the type of signature move that can help an institution define itself among its competitors, by becoming the leading steward of a powerful artist’s legacy.

Through this lens, the devil’s advocate might respond that there is little material difference between a museum’s owning ninety Chamberlain works or 100 Chamberlain works; the former would almost undoubtedly keep Dia at the apex of the artist’s institutional champions. But the raw numbers don’t tell the story accurately. In a vacuum, a ninety-deep Chamberlain collection would surely be a worthy asset to a museum’s branding efforts… but only if they collectedup to that number rather than slicing down to it. Deaccessioning can permanently invert the art world’s point of view. Thanks to Vergne, the ninety works Dia still holds now risk being permanently overshadowed by the ten they sold. Googling “Dia foundation + John Chamberlain” produces ten results on the opening page. Four are pro-Dia, with three of those from Dia itself; two are general bios of the artist; and four are about the deaccessioning scandal.

Further, there’s a willful blind spot in the “deaccession-to-diversify” argument: It presupposes that museum collecting is a zero-sum game. This is undeniably false. It is also the seed of the stigma surrounding deaccessioning. Acquiring new works to strengthen an institution is an admirable goal - and it also happens to be precisely what fundraising is for. There was no concrete need for Vergne to “prune” Dia’s holdings in 2013 because the foundation had enough physical space to accommodate new work, and the money to expand was available elsewhere. It would have required some pressing of the right flesh and stroking of the right egos, but it was there.

I don’t mean to oversimplify the job of fundraising; it is a difficult and often thankless pursuit. But it’s also the plasma that sustains all arts nonprofits, even major museums. Deaccessioning is not only a messy, temporary solution that evades this hard truth. It also risks crippling an institution’s chances of fundraising effectively once it decides to face reality. As I’ve written before, branding also matters to potential donors. Those who want to earn or maintain lofty standing in the art world are likely to think twice about opening the floodgates of charitable giving to a museum marred by a scandal it willfully brought onto itself. That makes deaccessioning a very human phenomenon: a short-term gain that ignores the long-term damage it could create.

There are even more market-based reasons that deaccessioning is ultimately an unwise strategy, but I have to save those for the next post. I fear I’ve already blown this one out to a length that will make people turn away in horror like the text actually forms an ASCII portrait of the Elephant Man. Til then…

Update: Jump to Part 2